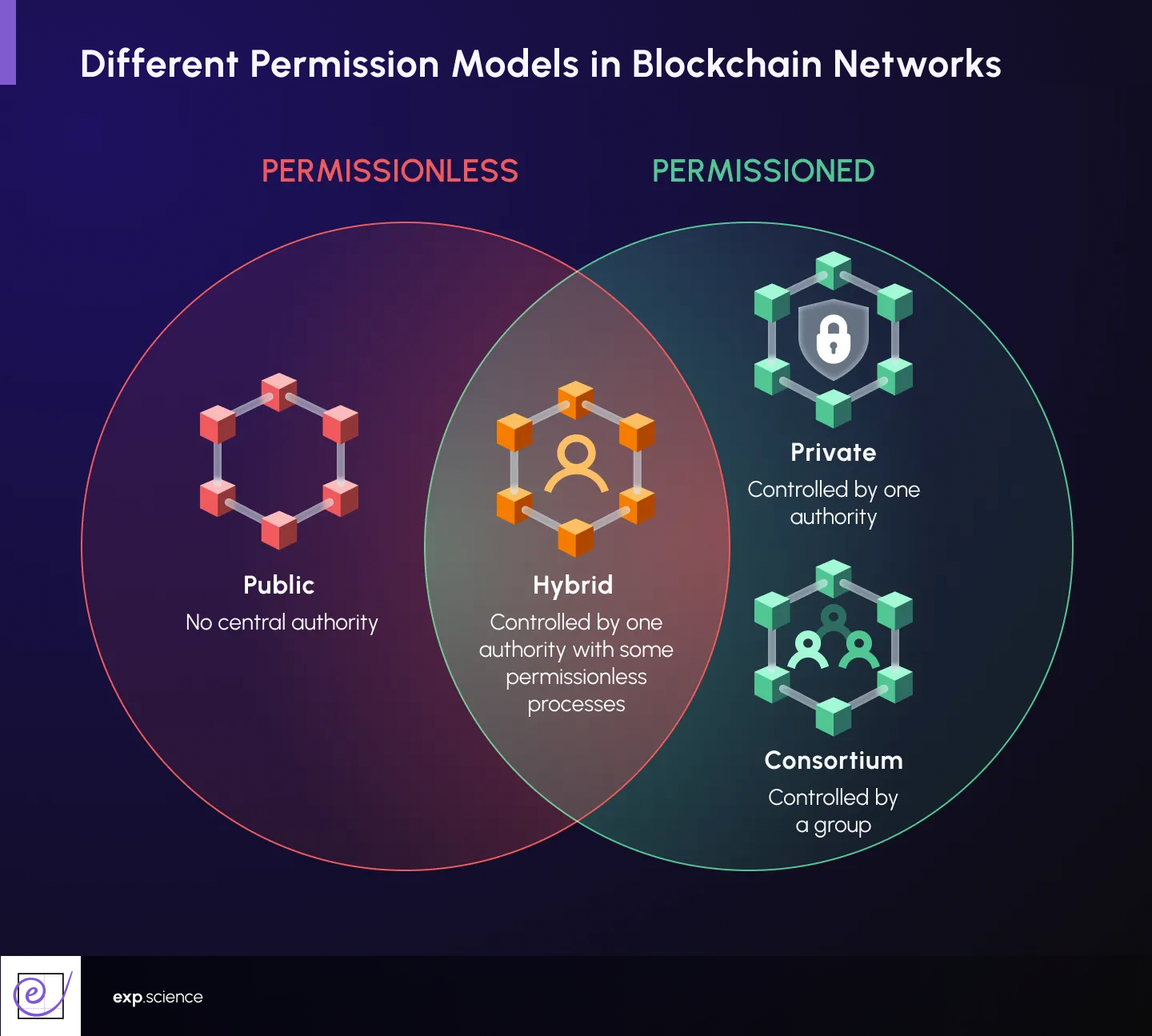

Permissioned and permissionless blockchains represent two different approaches to distributed ledger technology. Permissioned blockchains restrict access to a defined group of participants with controlled authority, whilst permissionless blockchains remain open to anyone with an internet connection, operating without central gatekeepers or predetermined hierarchies.

The permissioned model mirrors traditional institutional structures, trading openness for control and efficiency. The permissionless model embraces a democratic vision where rules are enforced by mathematics and consensus rather than human authority. Both have proven viable, yet they serve fundamentally different purposes and reflect divergent assumptions about how societies should organise themselves in the digital age.

The choice between these two architectures is rarely neutral. It shapes who can participate, who holds power, what information remains visible, and ultimately, whose interests the system serves. Understanding these differences requires looking beyond surface-level features to examine the tensions between openness and privacy, decentralisation and efficiency, and the eternal question of who should govern the systems we depend upon.

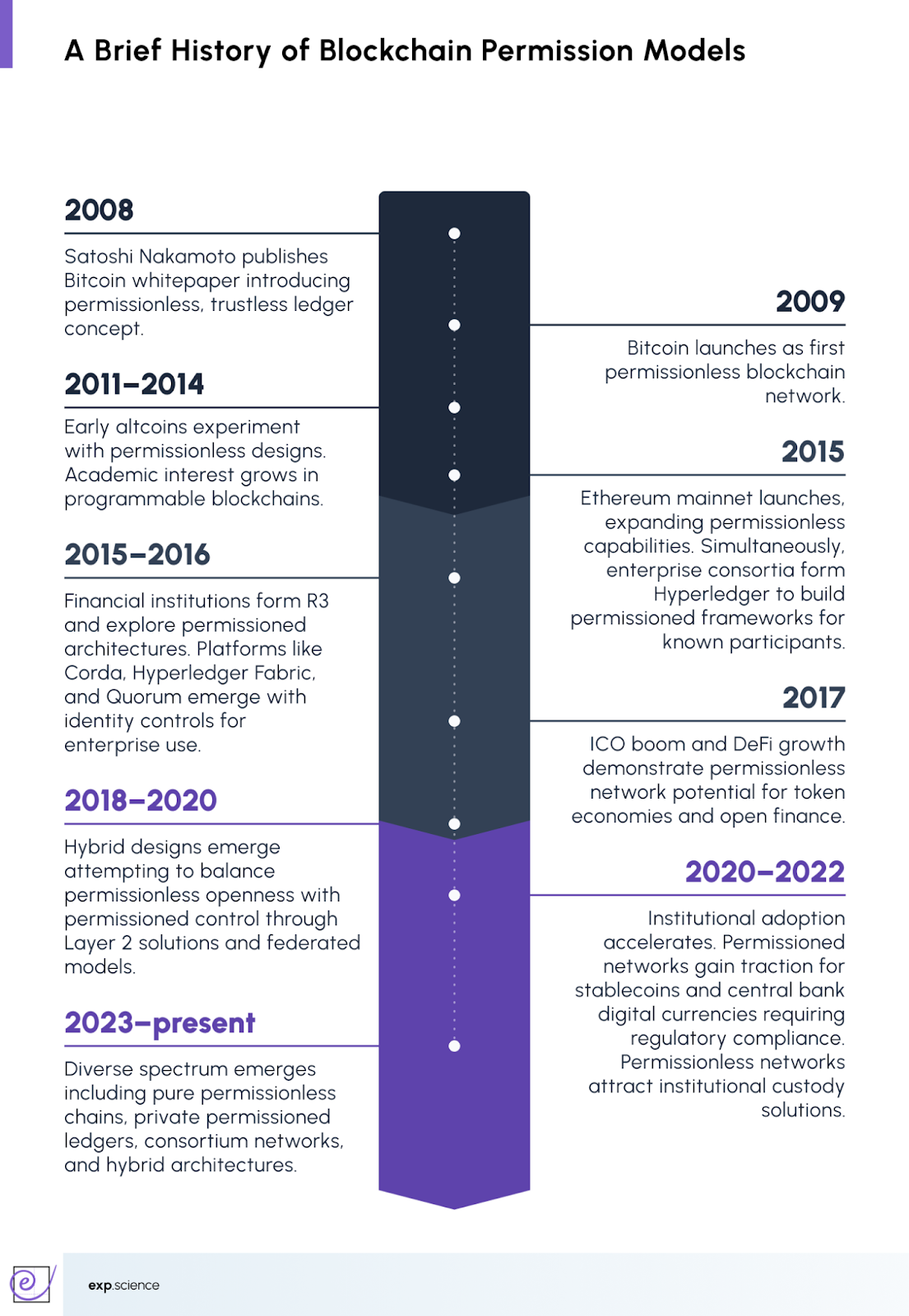

How Blockchain Technology Diverged

The concept of a blockchain, a chain of cryptographically linked blocks containing transaction data, first emerged from earlier work on timestamping digital documents. In 1991, researchers Stuart Haber and W. Scott Stornetta introduced blockchain technology, developing a system using cryptography to store time-stamped documents in a chain of blocks. However, the practical application of this technology remained largely theoretical until Satoshi Nakamoto's groundbreaking implementation.

Blockchain was officially introduced in 2009 with the release of its first application, the Bitcoin cryptocurrency. On 3rd January 2009, Nakamoto mined Bitcoin's genesis block, embedding within it a pointed message: ‘The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.’ This was more than a timestamp; it was a manifesto. Bitcoin's blockchain was designed to be radically open, permissionless by nature, allowing anyone to participate in validating transactions without seeking approval from any authority.

For several years, blockchain and Bitcoin were treated as synonymous. The architecture seemed inseparable from its anarchic, trustless ideology. Blockchain technology was separated from the currency around 2014, and its potential for other financial and inter-organisational transactions was explored, giving birth to Blockchain 2.0.

Financial institutions and enterprises began to recognise blockchain's potential but recoiled from its public, permissionless nature. They wanted the benefits: distributed consensus, tamper-evident records, reduced intermediaries, without the radical transparency and lack of control that characterised Bitcoin. This tension gave rise to the concept of permissioned blockchains.

In 2015, the Ethereum Frontier network launched, enabling developers to write smart contracts and decentralised applications, whilst the Linux Foundation and IBM launched the Hyperledger project, facilitating collaborative development of distributed ledgers for enterprise use. Hyperledger represented a departure from Bitcoin's ethos. It was explicitly non-cryptocurrency, designed for closed networks where known participants could transact with controlled privacy and governance structures. Hyperledger Fabric became one of the most widely adopted and influential enterprise frameworks for permissioned blockchains.

By 2016, the conceptual split was complete. The term ‘blockchain’ gained acceptance as a single word rather than two concepts, and major financial institutions formed consortia to explore blockchain for their operations. Two distinct paradigms emerged: permissionless blockchains, exemplified by Bitcoin and Ethereum, and permissioned blockchains, tailored for enterprise adoption. Each would evolve along separate trajectories, serving different masters and embodying different visions of what distributed trust could achieve.

The Architecture of Open Networks

Permissionless blockchains are open networks that require no authorisation to join. Anyone with internet access can participate in consensus mechanisms and create transactions, a radical accessibility that is both their greatest strength and challenge.

These networks rest on four principles.

- Transparency: every transaction is publicly verifiable through blockchain explorers, making transaction histories permanently visible despite pseudonymous participation.

- Decentralisation: no central authority exists; consensus protocols involve all participants, with rules enforced through mathematics rather than institutional policy.

- Pseudonymous participation: users are represented by cryptographic addresses rather than personal identification, but transaction patterns may reveal identities.

- Censorship resistance: distributed control makes censoring addresses or transactions extremely difficult, particularly valuable in authoritarian contexts.

Consensus mechanisms like Proof-of-Work (PoW) and Proof-of-Stake (PoS) make network attacks prohibitively expensive. Attacking the Bitcoin network would require controlling more computational power than the entire network, billions in hardware and energy costs. This economic security replaces institutional trust with mathematical certainty.

However, openness creates challenges. Permissionless blockchains suffer from lower transaction speeds. Bitcoin processes seven transactions per second versus Visa's thousands, due to resource-intensive consensus among thousands of participants. Ethereum has experienced congestion during high-demand periods, with transaction fees occasionally reaching hundreds of pounds.

The philosophical appeal is undeniable: mathematical rules govern access, censorship is structurally difficult, and transparency is enforced by design. Yet this purity creates practical challenges that have limited enterprise adoption.

The Controlled Alternative

Permissioned blockchains invert the assumptions of their permissionless counterparts. Users require permission from network owners to join and can only access, read, and write information if granted access. This gatekeeping fundamentally alters the system's properties. These closed networks, also known as private blockchains or permissioned sandboxes, involve previously designated parties who interact and participate in consensus. Participants are known entities, verified through traditional means before receiving network access. This transforms the trust model: instead of trusting mathematics and economic incentives, participants trust the gatekeepers controlling admission.

Governance differs markedly from permissionless systems. Rather than consensus-based decisions, a central authority or consortium determines who can join, what data they can access, and which actions they can perform. Whilst this hierarchy may seem antithetical to blockchain's decentralist ethos, it provides the control and accountability enterprises demand.

Consensus mechanisms reflect this different environment. Permissioned blockchains typically use Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance, federated consensus, or round robin consensus rather than proof of work. These mechanisms reach agreement much faster because they involve fewer participants and assume pre-established trust. Ten known banks can achieve consensus in seconds; ten thousand anonymous nodes cannot.

Transparency becomes optional. Transaction records can be kept private or hidden depending on the use case. Organisations may share certain data with partners while keeping competitive information confidential, impossible in public blockchains, where everything is visible. Performance benefits are substantial. Fewer nodes managing verification and consensus enable high transaction volumes comparable to traditional databases, while retaining blockchain's distributed consensus and tamper-evident records.

Permissioned blockchains trade radical decentralisation for enhanced privacy around sensitive information, making them viable for storing personal data legally required by regulations incompatible with public blockchains' transparency.

Yet trade-offs exist. Fewer participants create an increased risk of corruption and collusion, with consensus more easily overridden as owners can change rules. When a small group controls the network, they can rewrite history, alter consensus rules, or exclude network participants. The very control that makes permissioned blockchains useful also concentrates power in ways permissionless advocates find troubling.

Different Ideological Approaches to Trust and Governance

The technical differences between permissioned and permissionless blockchains are not simply engineering choices but expressions of fundamentally different worldviews.

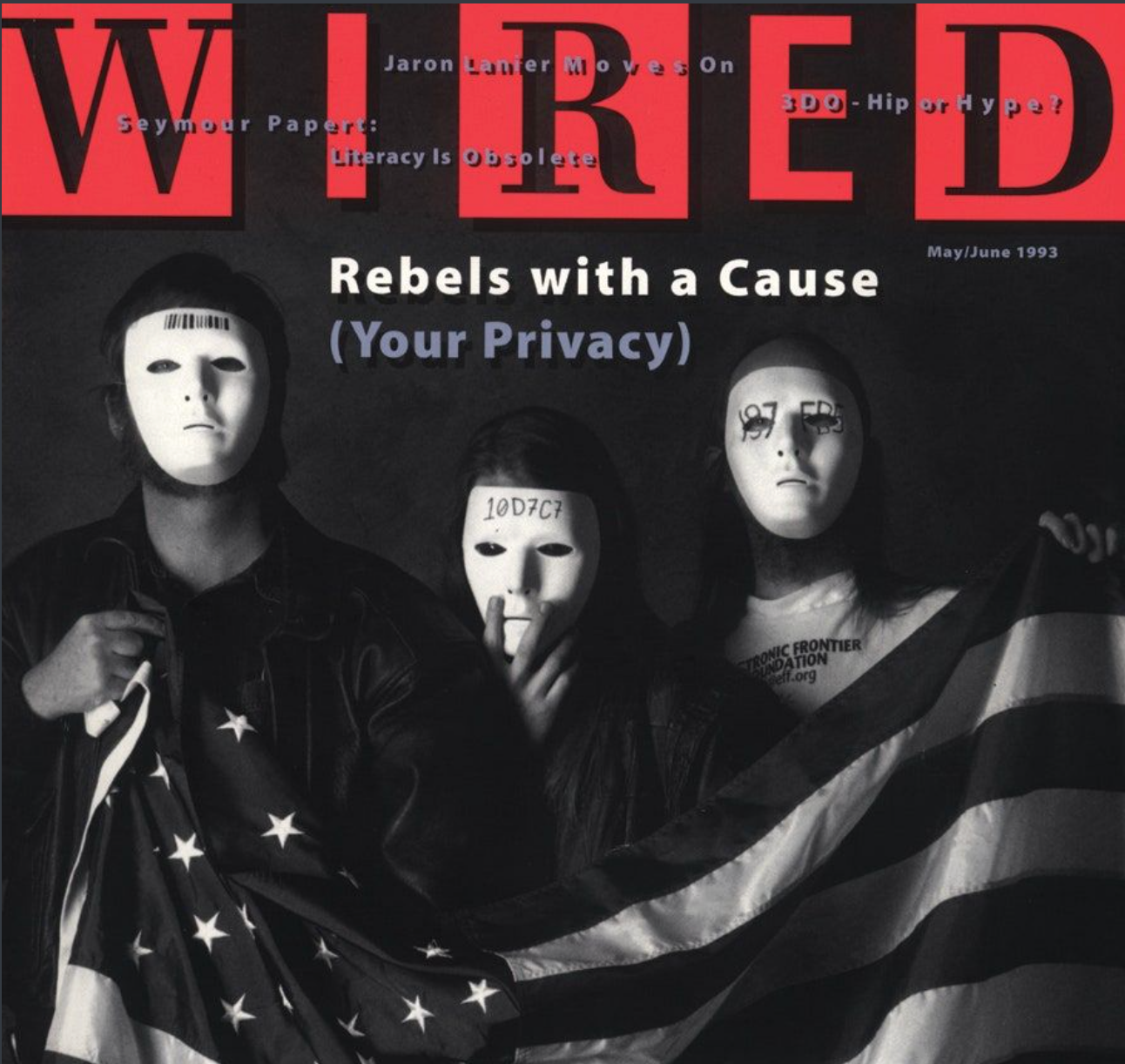

Permissionless blockchains embody a radical scepticism towards centralised authority. They assume that given sufficient power, institutions will abuse it, that banks will gamble with depositors' money, that governments will debase currencies, that gatekeepers will eventually serve their own interests rather than the common good. The solution is to eliminate gatekeepers entirely, replacing human discretion with algorithmic certainty.

This vision traces its lineage through the cypherpunk movement of the 1990s, which viewed cryptography as a tool for individual liberation from state and corporate control. Satoshi Nakamoto's embedding of a newspaper headline about bank bailouts in Bitcoin's genesis block was no accident; it was a declaration of principles. Permissionless blockchains are designed for a world where you cannot, and should not, trust authorities to act in your interest.

Yet this position carries its own costs and contradictions. Complete transparency means complete surveillance, at the very least, of transaction patterns. Irrevocability means mistakes cannot be corrected, thefts cannot be reversed, and harmful content published to the blockchain remains permanently accessible. The absence of governance means that when problems arise, resolution requires convincing thousands of independent actors to coordinate, a process that is slow, contentious, and often difficult to achieve.

Permissioned blockchains reflect a different ideology: that institutions, properly structured and accountable, can be trusted to manage shared infrastructure. That transparency should be calibrated to context rather than maximised by default. That governance requires human judgement, not just mathematical rules. That efficiency and pragmatism sometimes matter more than ideological purity.

This model accepts hierarchy as inevitable and potentially beneficial. It acknowledges that organisations need to comply with regulations, protect sensitive information, and maintain control over their operations. Rather than eliminating trusted third parties, permissioned blockchains seek to make them more accountable and efficient through distributed consensus and tamper-evident records.

Some researchers argue that permissioned blockchains in closed networks render chaining blocks unhelpful, as it's possible to recalculate all subsequent blocks in such networks, making altered blocks valid again. This critique suggests that without the openness and economic security of permissionless systems, blockchains may offer little advantage over traditional databases. If you trust the consortium running the network, why not simply use a more efficient centralised database?

The tension is between two visions of the future. One imagines a world of open protocols and distributed power, where individuals hold sovereignty over their digital lives independent of institutions. The other envisions institutions reformed and improved through technology, more transparent and accountable, but still fundamentally hierarchical.

Hybrid Models and the Future of Blockchain Architecture

The binary distinction between permissioned and permissionless is increasingly giving way to hybrid models that attempt to capture the benefits of both approaches whilst mitigating their respective weaknesses.

Layer-2 solutions represent one hybrid strategy. Networks like Bitcoin's Lightning Network or Ethereum's various scaling solutions maintain the security and decentralisation of the base permissionless layer whilst enabling faster, cheaper transactions through additional protocols. These systems enable users to conduct numerous transactions off-chain, only settling final states on the main blockchain. This preserves the permissionless base layer's censorship resistance while achieving transaction speeds comparable to the traditional payment systems.

Some projects have implemented permissioned access to certain functions whilst keeping core data publicly visible. Consortium blockchains allow predetermined organisations to validate transactions whilst making transaction records publicly auditable. This satisfies regulatory requirements for knowing participants' identities whilst maintaining transparency for outside observers. Central bank digital currencies, for instance, often contemplate architectures where only licensed financial institutions can validate transactions, but transaction records remain viewable to regulators and potentially the public.

Interoperability protocols aim to connect permissioned and permissionless networks, allowing value and data to flow between them. Enterprises might use private blockchains for internal operations whilst leveraging public blockchains for settlement or tokenisation. Healthcare records could remain on permissioned networks with strong privacy controls, yet generate anonymised research data published to public chains. Supply chain systems might track goods through private networks amongst known partners, then anchor key milestones to public blockchains for tamper-evident verification.

The technical challenges of such hybrid systems are significant. Security models differ fundamentally between architectures; bridging them introduces new vulnerabilities. Governance becomes more complex when multiple networks with different rules must coordinate. Yet the potential benefits drive continued experimentation and development.

Looking forward, blockchain architecture may evolve beyond the current paradigms entirely. Zero-knowledge proofs enable verification without revealing the underlying data, potentially allowing public blockchains to achieve transaction privacy previously possible only in permissioned systems. Advances in consensus mechanisms may address scalability limitations that currently force trade-offs between decentralisation and performance. Regulatory frameworks may clarify how different blockchain types should be treated, enabling new hybrid models that satisfy legal requirements whilst preserving decentralisation.

Two Paths, One Technology

Permissioned and permissionless blockchains represent fundamentally different answers to the same question: how should we organise trust in digital systems? One answer prioritises freedom, decentralisation, and individual sovereignty, accepting inefficiency and irrevocability as necessary costs. The other prioritises control, privacy, and institutional accountability, sacrificing radical openness for practical functionality.

Neither model is universally superior; each serves different needs and embodies different values. Permissionless blockchains will continue to power applications requiring censorship resistance and open participation: cryptocurrencies, decentralised finance, and systems designed to operate beyond institutional control. Permissioned blockchains will dominate enterprise contexts where efficiency, privacy, and regulatory compliance matter more than radical transparency.

The deeper significance lies not in the technical specifications but in what these architectures reveal about our assumptions and values. When we choose permissionless systems, we express scepticism towards centralised authority and faith in mathematical consensus. When we opt for permissioned networks, we acknowledge the continued role of institutions whilst seeking to make them more accountable through distributed technology.

In the end, blockchain technology, in all its forms, represents humanity's attempt to encode trust and coordination into software. Whether that software should be radically open or carefully controlled remains one of the defining questions of our digital age.

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.webp)

.jpg)