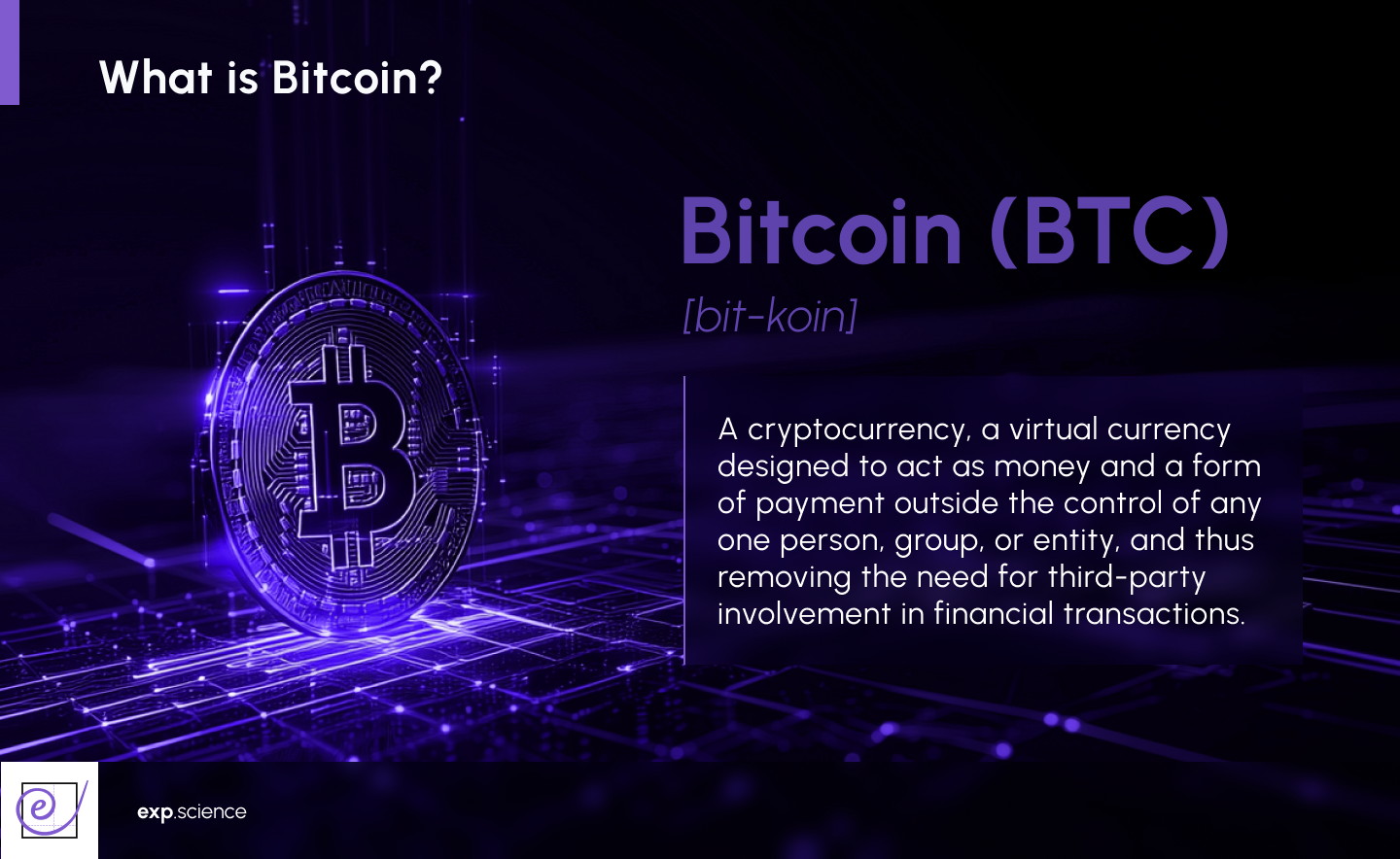

Bitcoin is a decentralised digital currency that operates independently of banks, governments, or central authorities. Since its inception in 2008, it has disrupted the traditional concepts of money, value storage, and financial control. Unlike conventional currencies issued and regulated by central banks, Bitcoin introduced a new paradigm: a trustless, borderless, and software-based form of money that anyone with an internet connection can use. It challenged long-held assumptions about who should govern financial systems and how transactions should be verified and recorded.

Today, Bitcoin is widely recognised and discussed across media, investment forums, and technology circles. Yet many are still unaware of why it was created, what problems it aimed to solve, and why its design remains radical over a decade later. Bitcoin is far more than a digital currency; it represents a comprehensive protocol combining a public ledger, a monetary policy, and a decentralised network, all operating without any central authority. This structure empowers users with unprecedented financial sovereignty and transparency.

To truly grasp Bitcoin’s significance requires moving beyond headlines and price charts. It demands an understanding of its technical architecture, ideological roots, and the profound implications it holds for the future of money and governance.

The Birth of Bitcoin

Bitcoin was introduced to the world on the 31st of October 2008 through a whitepaper titled Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System, published under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto. The paper proposed a solution to the long-standing problem of how to enable online payments directly between two parties without relying on a trusted third party, such as a bank or payment processor.

The timing was not incidental. The proposal emerged during the global financial crisis of 2007–2008, a period of extreme market volatility, widespread bank failures, and declining trust in centralised financial institutions. Bitcoin was presented as an alternative, both technically and philosophically, to a system many saw as opaque, fragile, and overly dependent on institutional trust.

On the 3rd of January 2009, Nakamoto mined the first Bitcoin block, known as the genesis block, which contained the now-famous embedded message:

"The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks."

This line from The Times newspaper was not only a timestamp; it was a commentary. It referenced a headline describing the UK government’s intention to rescue troubled banks with public funds, an act seen by many as socialising losses while privatising profits. Bitcoin’s design aimed to subvert this model entirely.

Where traditional banking requires users to place faith in a chain of intermediaries, each with the power to block transactions, charge fees, or fail entirely, Bitcoin offers a system of monetary interaction with no single point of failure. Transactions are verified by a distributed network of computers, all running open-source software and governed by rules that no single entity could alter. Instead of inflationary monetary policy set by central banks, Bitcoin introduces a capped supply and an issue rate that is generally predictable but subject to some variability, embedded directly into its codebase.

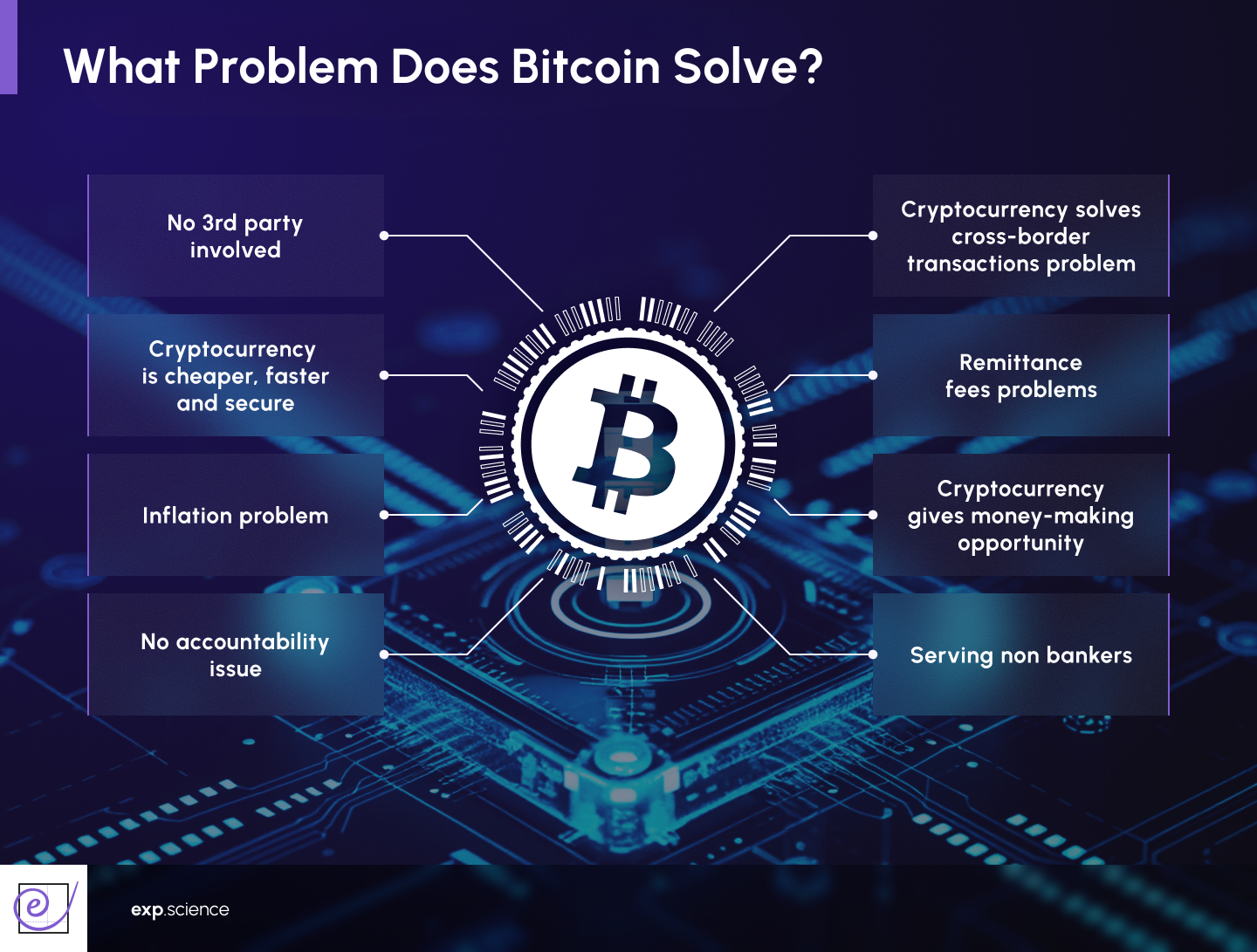

By eliminating the need for intermediaries, Bitcoin sought to address several core issues inherent to traditional finance: the double-spending problem, reliance on ‘trusted’ third parties, vulnerability to censorship or confiscation, restricted access in underbanked regions, and the need for a decentralised, peer-to-peer payment system without intermediaries. In contrast to the complexity of legacy banking systems, Bitcoin promised transparency, finality, and digital scarcity, accessible to anyone with an internet connection.

Taken together, these features made Bitcoin a radical alternative. It did not merely suggest improvements to financial infrastructure, it proposed a fundamental rethinking of what money is, how it should be issued, and who should control it.

What Problems Was Bitcoin Designed to Solve?

At its core, Bitcoin addresses several interrelated problems in traditional finance and digital trust:

1. The Double-Spending Problem

In digital systems, copying data is trivial. Before Bitcoin, attempts to create digital money failed because of the double-spending problem: how can a digital asset be spent once, and only once, without a central authority checking every transaction? Bitcoin solved this by using a distributed ledger and consensus mechanism to make every transaction publicly verifiable and immutable.

2. Reliance on Trusted Third Parties

Traditional digital payments often rely on intermediaries such as banks and credit card networks, which can introduce friction, fees, censorship, and systemic risk. For instance, in 2022, Visa and Mastercard suspended operations in Russia in response to international sanctions.

This decision rendered cards issued by Russian banks unusable for international transactions, effectively isolating Russian consumers from the global financial system.

Bitcoin, by contrast, operates on a decentralised network that doesn't depend on central authorities or intermediaries. This structure enables users to send and receive payments globally without the risk of being cut off due to geopolitical events or institutional policies.

3. Monetary Policy Control

Central banks have the power to print money on demand, giving them significant control over the economy and, by extension, everyone’s financial well-being. This discretionary ability can lead to inflation or currency devaluation, which erodes purchasing power and can destabilise entire economies, as seen in cases of hyperinflation worldwide.

In contrast, Bitcoin enforces a strict monetary policy embedded in its code: only 21 million Bitcoin will ever exist. New Bitcoin are issued on a fixed, predictable schedule through mining, with rewards halving approximately every four years until the last coin is mined around 2140.

This algorithmic scarcity provides transparency and certainty, positioning Bitcoin as a deflationary asset, often called ‘digital gold.’ By removing human discretion from money creation, Bitcoin offers resistance to inflation and political interference, marking a fundamental shift from traditional fiat currencies and the centralised economic control they represent.

How Does Bitcoin Work?

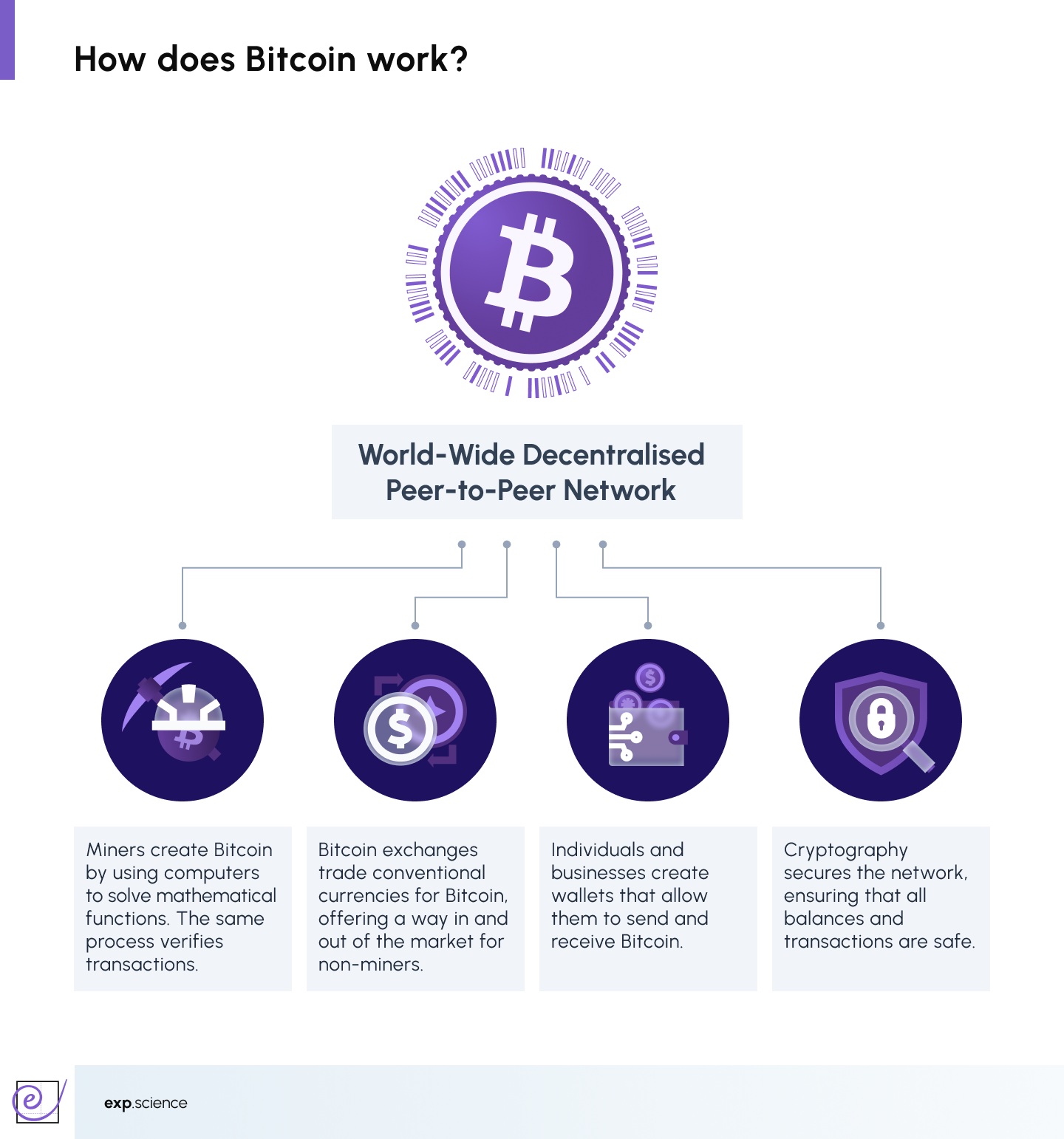

Bitcoin operates through a combination of technologies that together enable a trustless, peer-to-peer monetary system. It is built on the foundational principles of distributed ledger technology (DLT), which evolved to create a secure, transparent, and decentralised record of transactions without relying on a central authority. The core components are as follows:

1. Blockchain

Bitcoin’s ledger is maintained through a structure called a blockchain: a chronological chain of blocks, each containing a set of transactions. Every block includes a reference (a cryptographic hash) to the previous block, forming a tamper-evident history of all activity on the network. Once added to the chain, data cannot be altered without redoing the proof-of-work for that block and all subsequent blocks, a computationally infeasible task.

2. Proof-of-Work (PoW)

To add a new block to the chain, network participants known as miners must compete to solve a complex mathematical puzzle. Miners are a specialised subset of nodes that expend computational effort to create and propose new blocks. The first miner to solve the puzzle (the ‘proof-of-work’ or PoW) earns a reward in new Bitcoin and collects transaction fees as well as a block subsidy. Although proof-of-work mechanisms existed before Bitcoin (notably in Hashcash), the idea of specialised miners competing for rewards within a decentralised network was new. Miners receive financial compensation for their work, while node operators support decentralisation without direct monetary incentives.

If the miner is malicious, the block will be rejected by the honest majority of nodes, wasting the substantial computational effort made, which deters malicious actors and ensures network security. This process is known as ‘Nakamoto Consensus.’

3. Decentralised Nodes

Bitcoin’s ledger is not stored in a single location. Instead, tens of thousands of nodes, computers running Bitcoin software, maintain copies of the blockchain and enforce the protocol’s rules. This ensures the network’s resilience to attacks or censorship and allows anyone to audit the entire history of the system. Anyone can run a node, contributing to the network’s decentralisation and independently verifying transactions.

Nodes form the backbone of the Bitcoin network, but not all nodes perform the same functions. Mining nodes compete to mine blocks and earn block rewards, while non-mining nodes validate transactions, relay them across the network, and maintain the blockchain's records without participating in block production. This clear separation between block production and transaction validation was a key innovation of Bitcoin.

4. Private and Public Keys

Users interact with Bitcoin using cryptographic key pairs. A private key is used to sign transactions and prove ownership of funds, while a public key (or its hash, the address) is shared to receive payments. This model enables secure, pseudonymous transactions without disclosing personal identities. However, if users lose their private keys, they permanently lose access to their funds, as there is no central authority to recover or reset them.

How is Bitcoin Different from TradFi?

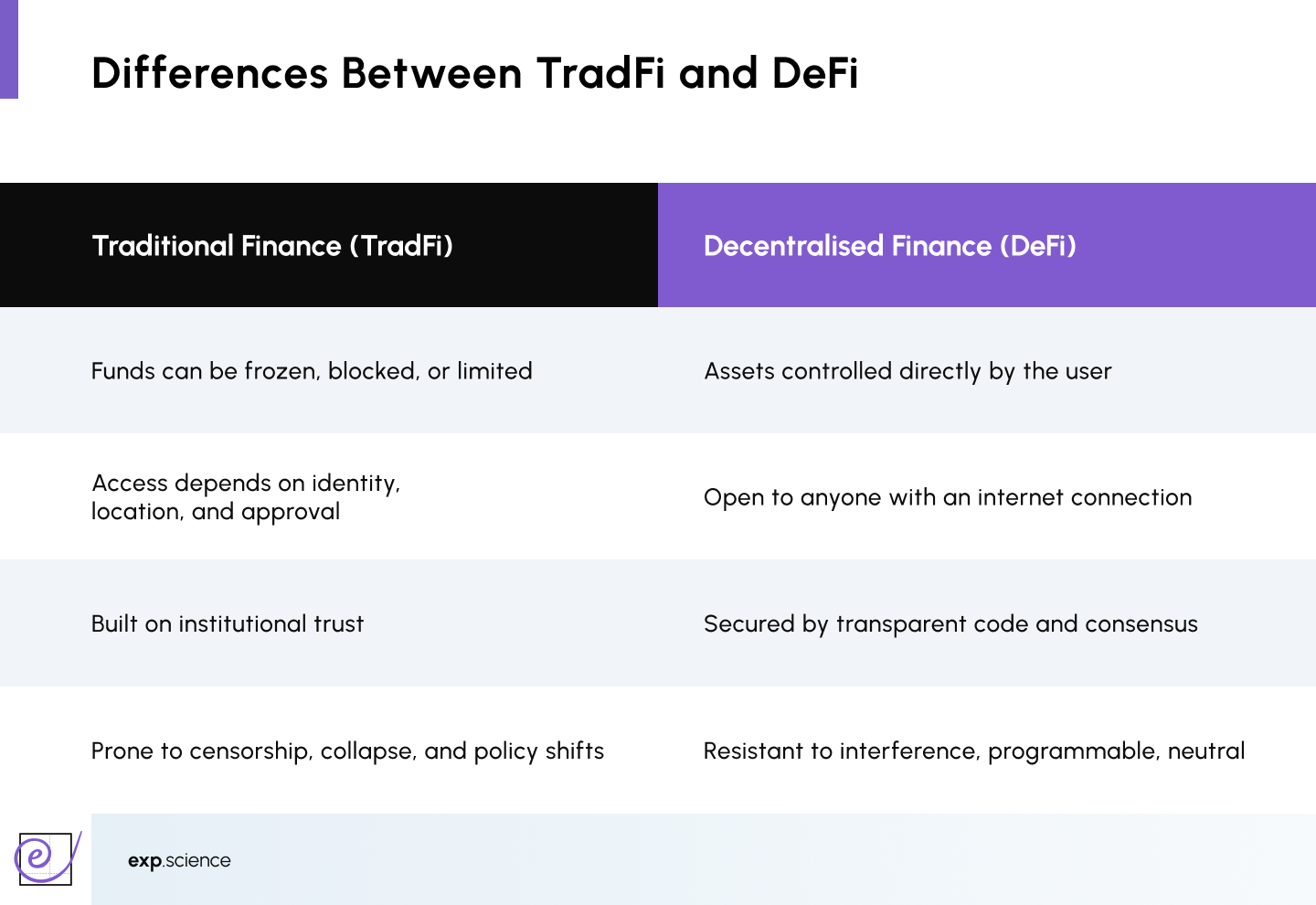

Bitcoin’s most impactful aspect was not any single technological component, digital signatures, hash functions, and peer-to-peer networks all pre-existed, but the integration of these components into a self-governing, decentralised monetary system.

For the first time, a digital asset could be transferred without requiring any central authority or intermediary. Scarcity, a property previously impossible to ensure in digital environments, became enforceable through protocol rules and consensus. Bitcoin was the first practical implementation of money existing purely as software, without needing banks, states, TTPs, or physical commodities to back it.

This decentralisation makes Bitcoin remarkably resilient. No government, corporation, or developer can unilaterally alter its monetary policy, freeze accounts, reverse transactions, or censor activity. All changes must be accepted by a critical mass of the network’s participants, a level of democratic coordination rare in financial infrastructure.

This model stands in sharp contrast to traditional finance. In conventional banking systems, central authorities such as commercial banks or monetary regulators have wide-ranging control. They can delay, block, or reverse transactions, impose capital controls, and even confiscate funds. Individuals must trust that their bank will not misuse their deposits and hope that the bank itself remains solvent.

These risks are not theoretical, as during the 2015 eurozone debt crisis, the Greek government imposed capital controls to prevent money from leaving the country. Banks were temporarily closed, and individuals could withdraw only limited amounts of cash from ATMs. Depositors had no access to the bulk of their own money, not because of fraud or error, but because of government policy and systemic fragility.

Similar instances have occurred in Lebanon, where informal capital controls imposed by commercial banks meant citizens could access as little as $400 USD per month of their own money. Some turned to armed robbery of their own banks to access their life savings. In Nigeria, the 2023 currency redesign triggered nationwide cash shortages and strict withdrawal limits, preventing millions from accessing their funds when they needed them most.

Bitcoin offers a stark alternative since users control their own private keys and funds held on the Bitcoin network cannot be seized, frozen, or devalued by decree. There is no central vault to raid, no switch to flip. Ownership of Bitcoin is enforced not by trust in institutions but by cryptographic proof and decentralised consensus. This design makes Bitcoin especially valuable in regions facing inflation, political instability, or banking restrictions.

How is Bitcoin Decentralised?

At the heart of Bitcoin lies an idea that money can exist without a central authority. Decentralisation is not just a technical feature, it is a foundational principle designed to resist control, censorship, and single points of failure. Decentralisation in Bitcoin exists at multiple levels:

- Network Infrastructure: Tens of thousands of independently operated nodes maintain the protocol, validate transactions, and distribute the blockchain.

- Mining and Consensus: While mining has become more industrialised over time, no single entity controls the process. Miners are free to enter and exit the network and must follow the protocol’s consensus rules.

- Open Source Code: Bitcoin’s codebase is publicly available and maintained by a community of developers. Any changes must gain widespread support across the ecosystem to be adopted.

- Governance by Consensus: Bitcoin does not rely on formal governance structures. Instead, upgrades and proposals are debated and adopted voluntarily, often only after significant discussion and testing.

Bitcoin Use Cases and Adoption

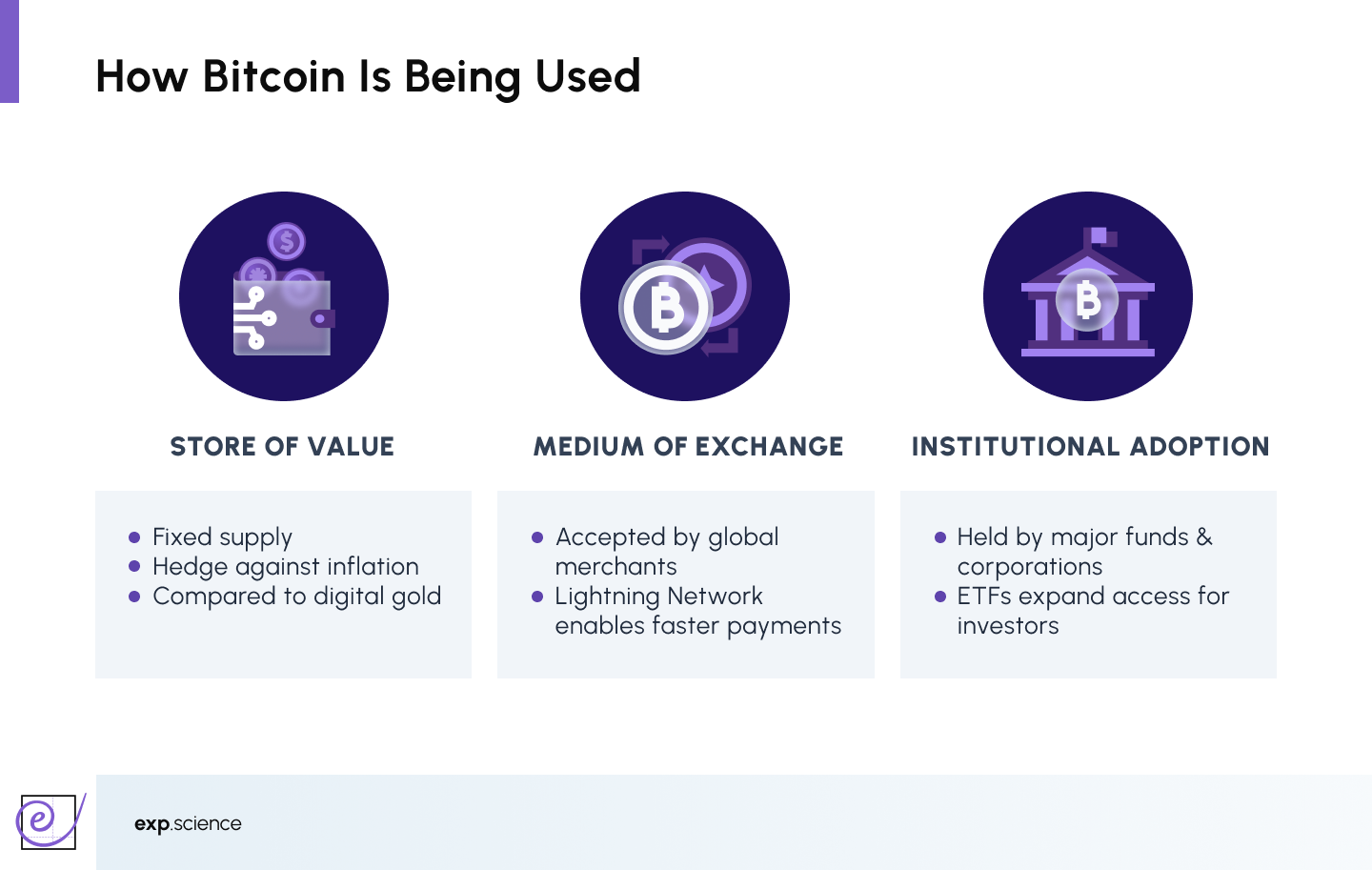

Bitcoin’s versatility has driven a range of use cases, evolving from a novel experiment into a globally recognised financial asset.

Store of Value

Bitcoin is widely regarded as a digital store of value. Its capped supply and algorithmic scarcity have drawn comparisons to precious metals like gold. Investors use Bitcoin to hedge against inflation and currency debasement, particularly in countries facing economic instability or hyperinflation. Over time, it has gained acceptance as “digital gold,” valued for its durability, divisibility, and resistance to censorship or seizure.

Medium of Exchange

While Bitcoin’s primary reputation is as a store of value, it was initially designed to function as a peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Although some merchants do accept Bitcoin payments, adoption for direct transactions remains relatively niche, with most commercial acceptance occurring through payment processors that immediately convert BTC to traditional currency.

This limited adoption as a medium of exchange stems from several challenges: price volatility, fee spikes, and relatively slow transaction speeds compared to traditional payment systems all hinder Bitcoin’s use as everyday currency. Layer-2 solutions like the Lightning Network aim to address these issues by enabling faster and cheaper transactions, potentially expanding Bitcoin’s utility for everyday payments.

Institutional Adoption and ETFs

Bitcoin has witnessed significant institutional interest over the past decade. Major companies, hedge funds, and asset managers have allocated capital to Bitcoin as part of diversified portfolios, recognising its unique risk-return profile. This institutional acceptance has been further bolstered by the introduction of Bitcoin exchange-traded funds (ETFs) in various jurisdictions, which provide regulated and accessible investment vehicles. ETFs enable investors to gain exposure to Bitcoin’s price movements without directly holding the cryptocurrency, broadening adoption among retail and institutional investors alike.

Together, these use cases illustrate Bitcoin’s growing influence across the financial ecosystem, balancing its roles as a speculative asset, payment method, and emerging pillar of modern finance.

How Bitcoin Compares to Other Cryptocurrencies

Bitcoin is the first and most widely adopted cryptocurrency, but it is far from the only one. Since its launch, thousands of digital assets have emerged—some competing directly with Bitcoin, others pursuing different use cases.

Key differences include:

- Purpose: Bitcoin’s primary function is as a store of value and medium of exchange. Other cryptocurrencies, such as Ethereum, prioritise programmability and support for decentralised applications.

- Consensus Mechanism: While Bitcoin uses energy-intensive proof-of-work, many newer networks adopt proof-of-stake (PoS) or other mechanisms that reduce energy usage.

- Throughput and Speed: Bitcoin’s base layer processes about 7 transactions per second. Other blockchains may offer higher throughput but often sacrifice decentralisation or security.

- Monetary Policy: Bitcoin’s capped supply is a distinctive feature among major cryptocurrencies, setting it apart from other cryptocurrencies that have more inflationary or flexible models.

Despite newer innovations, Bitcoin remains the benchmark and retains the largest market capitalisation, network security, and brand recognition.

Advantages of Bitcoin

- Censorship Resistance: No central authority can block transactions or freeze funds.

- Scarcity: With a maximum supply of 21 million coins, Bitcoin offers a predictable monetary model with deflationary trends.

- Security: The Bitcoin network is secured by an immense amount of computational power, making it highly resistant to attack.

- Global Accessibility: Bitcoin can be accessed and used by anyone with an internet connection, regardless of their geographical location or political environment.

- Transparency: All transactions are publicly verifiable on the blockchain.

Disadvantages and Limitations

- Energy Consumption: Bitcoin’s proof-of-work mining requires significant energy, leading to environmental concerns and debates about sustainability.

- Scalability: The base layer has limited capacity, leading to congestion and high fees during periods of peak demand.

- Volatility: The price of Bitcoin can fluctuate significantly, which complicates its use as a stable medium of exchange.

- Regulatory Uncertainty: Governments worldwide continue to grapple with how to regulate Bitcoin, with approaches ranging from full embrace to outright bans.

- Technical Barrier: Securely managing private keys and navigating decentralised systems requires a level of digital literacy that is not yet widespread.

The Energy Debate: Proof-of-Work vs Alternatives

One of the most persistent criticisms of Bitcoin centres on its substantial energy consumption. The network’s underlying consensus mechanism, proof-of-work, deliberately requires vast amounts of computational power—and consequently electricity—to secure the blockchain. This process involves miners solving complex cryptographic puzzles to validate transactions and add new blocks to the ledger. According to some estimates, Bitcoin’s annual energy consumption exceeds that of entire countries, drawing significant scrutiny from environmental advocates and policymakers alike.

Supporters of Bitcoin argue that this energy expenditure is a necessary trade-off for the level of security, censorship resistance, and decentralisation it provides. The intensive computational work deters malicious actors by making attacks prohibitively expensive and resource-intensive. In this view, the electricity consumed underpins a trustless system that operates without reliance on central authorities or intermediaries, making Bitcoin uniquely robust and resilient.

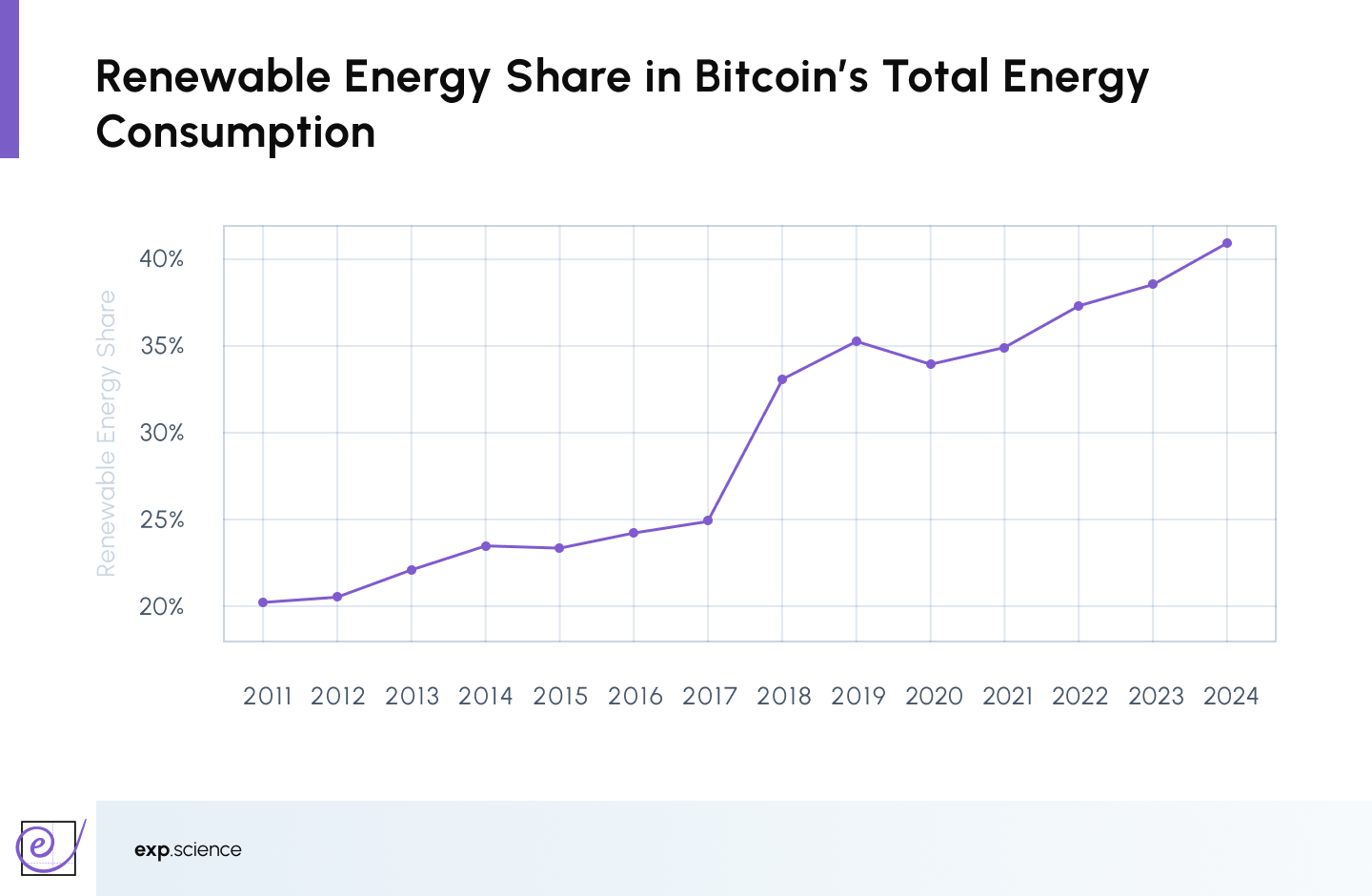

However, recent data from the MiCA Crypto Alliance’s report Mining the Future and a study from the University of Cambridge reveal that Bitcoin is more sustainable than often portrayed. Its reliance on renewable energy has nearly doubled since 2011, reaching approximately 41%, while coal usage has declined significantly. Projections suggest that by 2030, at least 70% of Bitcoin mining will be powered by renewables, indicating a potential substantial reduction in its environmental impact.

[Source: MiCA Crypto Alliance, Mining the Future report (2025)]

The blockchain community has developed various consensus mechanisms beyond PoW, including proof-of-stake, which takes a fundamentally different approach to network validation. Unlike PoW, PoS typically requires validators to commit (or ‘stake’) their tokens as collateral to participate in transaction validation, rather than expend computational energy. This model reduces energy usage dramatically as it eliminates the need for power-hungry mining equipment.

Ethereum, the second-largest blockchain network by market capitalisation, originally used proof-of-work, similar to Bitcoin. However, in September 2022, it transitioned to proof-of-stake in a landmark upgrade known as ‘The Merge.’ This shift reduced Ethereum’s energy consumption by over 99%, setting a precedent for sustainable blockchain operation while maintaining network security and decentralisation.

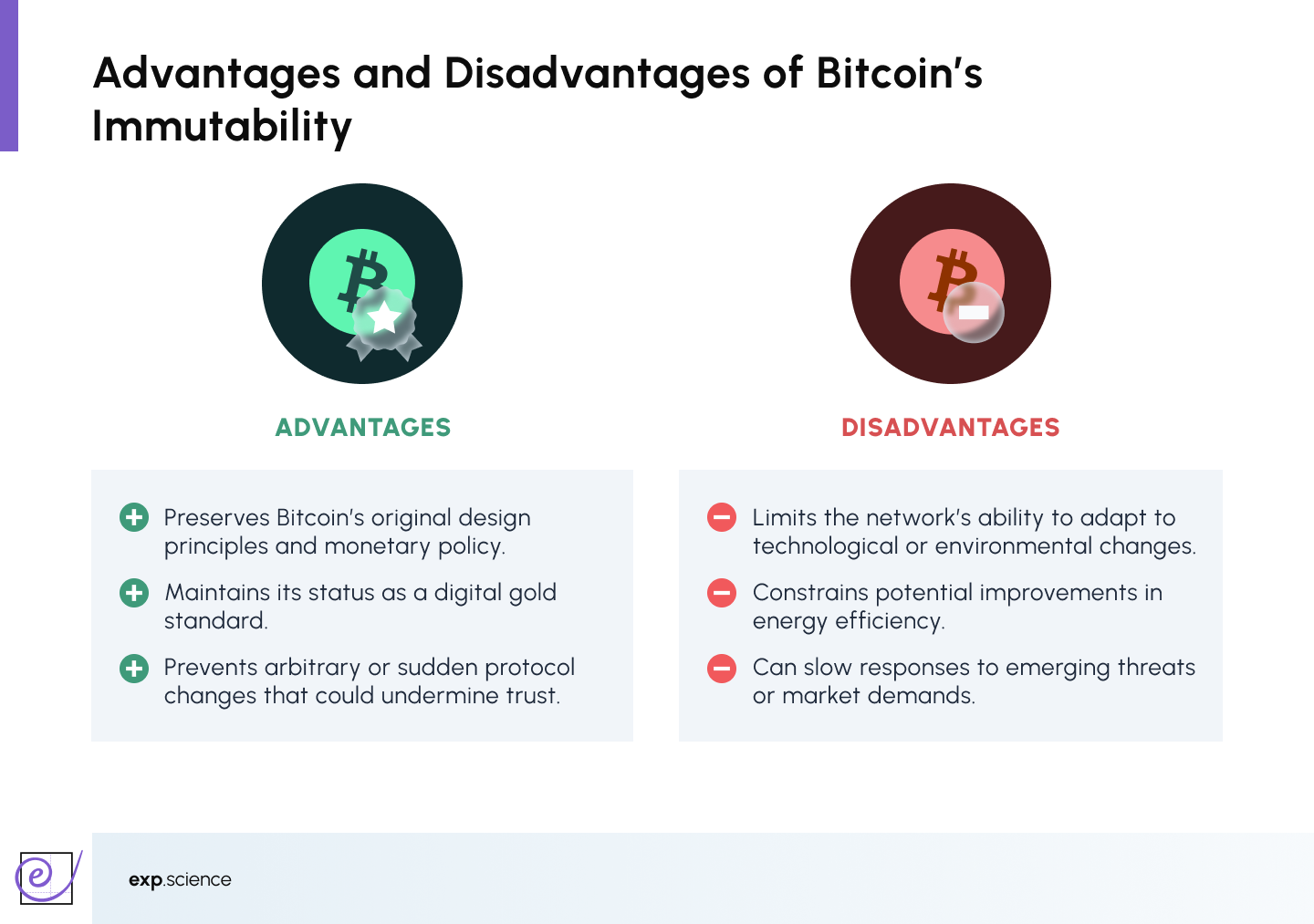

Bitcoin, by contrast, cannot simply switch consensus mechanisms. Its protocol is famously immutable, any fundamental change, such as moving from proof-of-work to proof-of-stake, would require overwhelming consensus from node operators, a coordination challenge of unprecedented scale. This rigidity is a double-edged sword:

Beyond Bitcoin and Ethereum, other distributed ledger technologies have pioneered alternative approaches that deliver high throughput with lower energy costs. Hedera Hashgraph, for example, employs a “gossip-about-gossip” PoS protocol combined with asynchronous Byzantine Fault Tolerance (aBFT) consensus. This architecture achieves fast finality and strong security guarantees without the energy-intensive computations characteristic of proof-of-work. As a result, Hedera operates with a fraction of Bitcoin’s carbon footprint, appealing to enterprises and applications where sustainability is a critical consideration.

The energy debate surrounding Bitcoin underscores a broader tension in blockchain design: balancing security, decentralisation, and sustainability. While Bitcoin’s proof-of-work has proven remarkably secure and censorship-resistant over more than a decade, its environmental impact drives ongoing exploration of alternative consensus mechanisms better suited for the future’s energy-conscious landscape.

Who Created Bitcoin?

The true identity of Bitcoin's creator remains one of the most intriguing mysteries in modern technology. On October 31, 2008, the Bitcoin whitepaper was shared by 'Satoshi Nakamoto' via the Cryptography Mailing List on metzdowd.com, a public forum frequented by cryptographers and cypherpunks—under the subject line ‘Bitcoin P2P e-cash paper,’ with a link to download it from Bitcoin.org.

On January 3, 2009, Nakamoto released the first implementation of the Bitcoin software and mined the first block of the chain. Nakamoto's choice to embed the message 'The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks' in Bitcoin's genesis block revealed something important about the creator's motivations. It was a pointed critique of the traditional financial system and a signal of Bitcoin's intended purpose—to serve as an alternative to centralised, bailout-prone monetary systems.

Despite ongoing speculation, Nakamoto's identity has never been conclusively verified. Over the years, various individuals have been suspected or have claimed to be Nakamoto, but none have provided irrefutable proof. What is known is that Nakamoto was active in the early development of Bitcoin—communicating with other developers, posting in forums, and contributing code until gradually stepping back in 2010 and eventually disappearing from public view entirely by 2011.

Estimates suggest that Nakamoto mined over one million Bitcoin in the early days, much of which remains untouched. These holdings, representing billions of dollars in today’s value, have never been moved, adding further to the enigma and mythology surrounding Bitcoin’s origin.

Importantly, Bitcoin was designed in such a way that the identity of its creator is irrelevant to the system’s long-term operation. Unlike traditional projects with a central figurehead or leadership structure, Bitcoin runs on open-source code and decentralised consensus. No single individual, including Nakamoto, can control its monetary policy or development direction.

Nakamoto's anonymity, combined with the open and decentralised nature of the protocol, has contributed to Bitcoin’s credibility as a politically neutral monetary system. Whether the creator was a lone genius, a small group of developers, or a team backed by an institution, their decision to remain anonymous and to relinquish control may have been one of the most important design choices of all.

What is Bitcoin Halving?

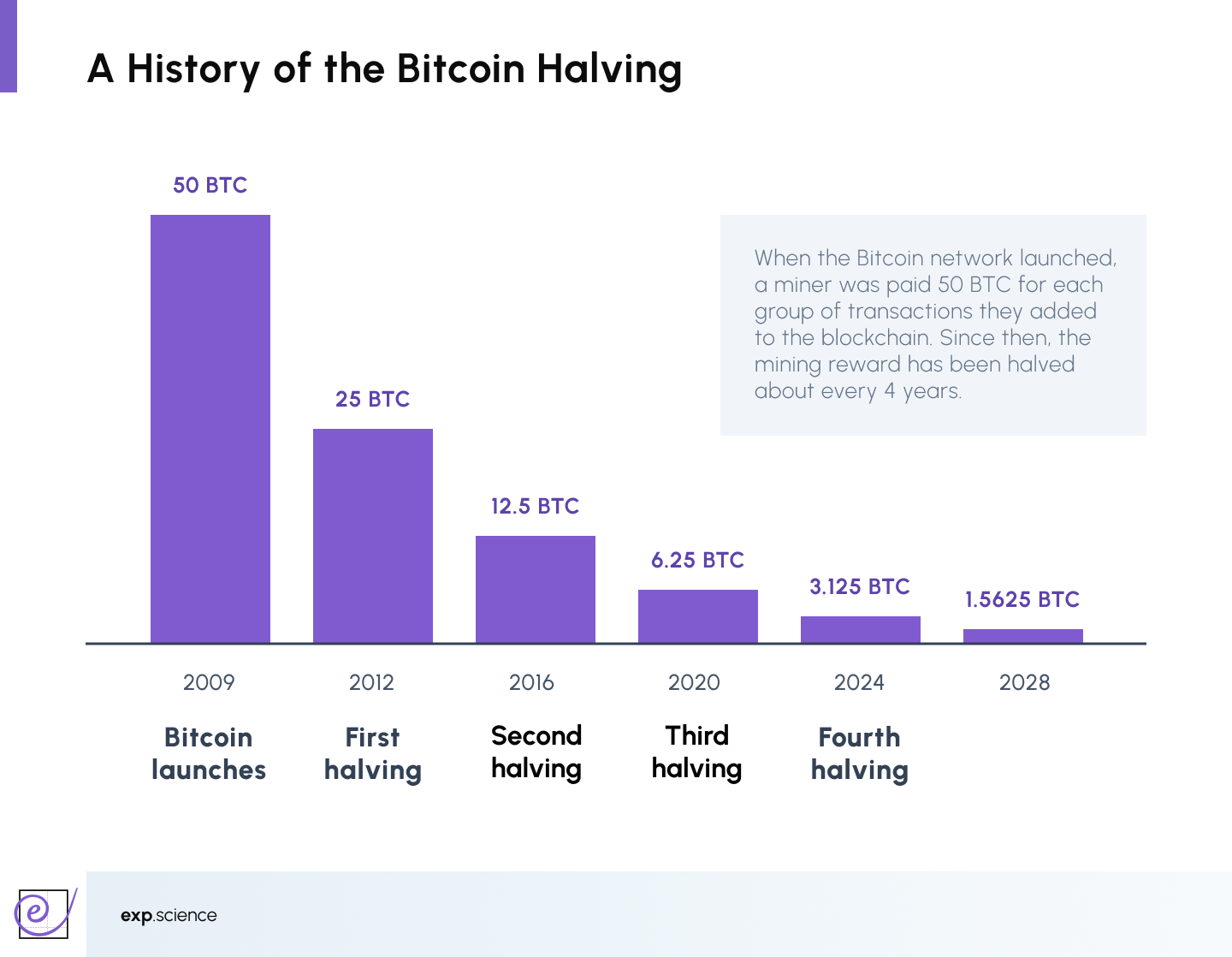

Bitcoin halving is a built-in event that occurs approximately every 210,000 blocks, or roughly every four years, where the block reward given to miners for validating transactions is cut in half. When Bitcoin launched in 2009, miners received 50 Bitcoin per block. The first halving in November 2012 reduced this reward to 25 Bitcoin, followed by the second in July 2016, dropping it to 12.5 Bitcoin.

The most recent Bitcoin halving occurred on April 20, 2024, at block height 840,000, reducing the block reward from 6.25 BTC to 3.125 BTC. The next halving is expected around April 17, 2028, at block height 1,050,000, when the reward will decrease to 1.5625 BTC per block.

This mechanism controls the rate at which new Bitcoin enters circulation, ensuring the total supply will never exceed 21 million coins. By gradually reducing the issuance of new Bitcoin, halving events introduce scarcity and help protect against inflation within the network. Historically, halvings have often preceded significant price increases, reflecting shifts in supply and demand dynamics. For example, after the 2012 halving, Bitcoin’s price surged from around $12 to over $1,000 within a year. Similarly, following the 2016 and 2020 halvings, Bitcoin experienced major rallies, reaching new all-time highs.

Bitcoin halving is therefore a fundamental part of the protocol’s design, enforcing predictable scarcity and shaping the economic incentives for miners and participants in the network over time.

Where Crypto Began

Bitcoin is more than a speculative asset or a payment system. It represents a paradigm shift in how value can be created, transferred, and governed. By enabling trustless transactions, enforcing digital scarcity, and operating without central control, Bitcoin has redefined the possibilities of finance and decentralisation.

Yet it is not without trade-offs. Its architecture prioritises security and immutability over speed and energy efficiency. As the digital asset landscape matures, Bitcoin continues to serve as the foundational reference point—respected, imitated, and debated in equal measure.

Its legacy is already evident in the emergence of thousands of alternative protocols and the rethinking of central bank policies, financial infrastructure, and the nature of money itself.

Disclaimer: This article provides educational information about Bitcoin and should not be considered financial advice. Cryptocurrency investments carry significant risks, and readers should conduct their own research before making any investment decisions.

.jpg)

.webp)

.jpg)