Tokenomics lies at the heart of every digital asset ecosystem. It defines not only how tokens function but also how they generate, retain, and distribute value within a decentralised system. Short for ‘token economics,’ the term blends elements of monetary policy, behavioural game theory, and system design —all encoded within blockchain protocols.

Where traditional economies rely on central banks to establish policies for issuance, interest, and inflation, tokenomics replaces that framework with open-source, automated logic. Whether building, investing, or analysing projects, understanding tokenomics is vital for those involved in crypto to evaluate a project’s potential for growth, sustainability, and decentralisation.

Effective tokenomics can drive a project’s success; flawed tokenomics, on the other hand, can undermine it, regardless of the project's innovation or marketing efforts.

What Is Tokenomics?

At its foundation, tokenomics refers to the economic principles and incentive mechanisms embedded in blockchain protocols that govern a digital asset’s lifecycle. These include how tokens are minted, distributed, utilised, and removed from circulation.

Unlike fiat systems, subject to frequent changes driven by political agendas or economic instability, tokenomics operates through preset logic defined in code and smart contracts. This creates consistency, transparency, and predictability over time.

But tokenomics goes beyond regulating supply and demand. It sets the behavioural framework for users: rewarding contributors, encouraging security, and deterring malicious activity. It also provides a structure for the micro-economy of a blockchain, aligning developers, token-holders, investors, and users by tying value creation directly to participation and usage. Poor tokenomics can lead to loss of community confidence or asset depreciation; well-designed frameworks, conversely, foster network growth and resilience.

Before proceeding further, it is worth distinguishing between two commonly confused terms:

- Coins (like Bitcoin or Ether): These are native to their own blockchains and primarily function as digital currencies. They are normally used for transferring value, securing networks through mining or staking, or paying transaction fees within their ecosystem.

- Tokens: Built on top of existing blockchains (such as Ethereum, Solana, TRON or BNB Chain), using smart contract standards (e.g., ERC-20, SPL). Tokens can represent access rights, governance power, digital or physical assets, or services within a given application or protocol.

Although tokenomics usually centres on tokens, the underlying economic principles are often applicable to native coins as well.

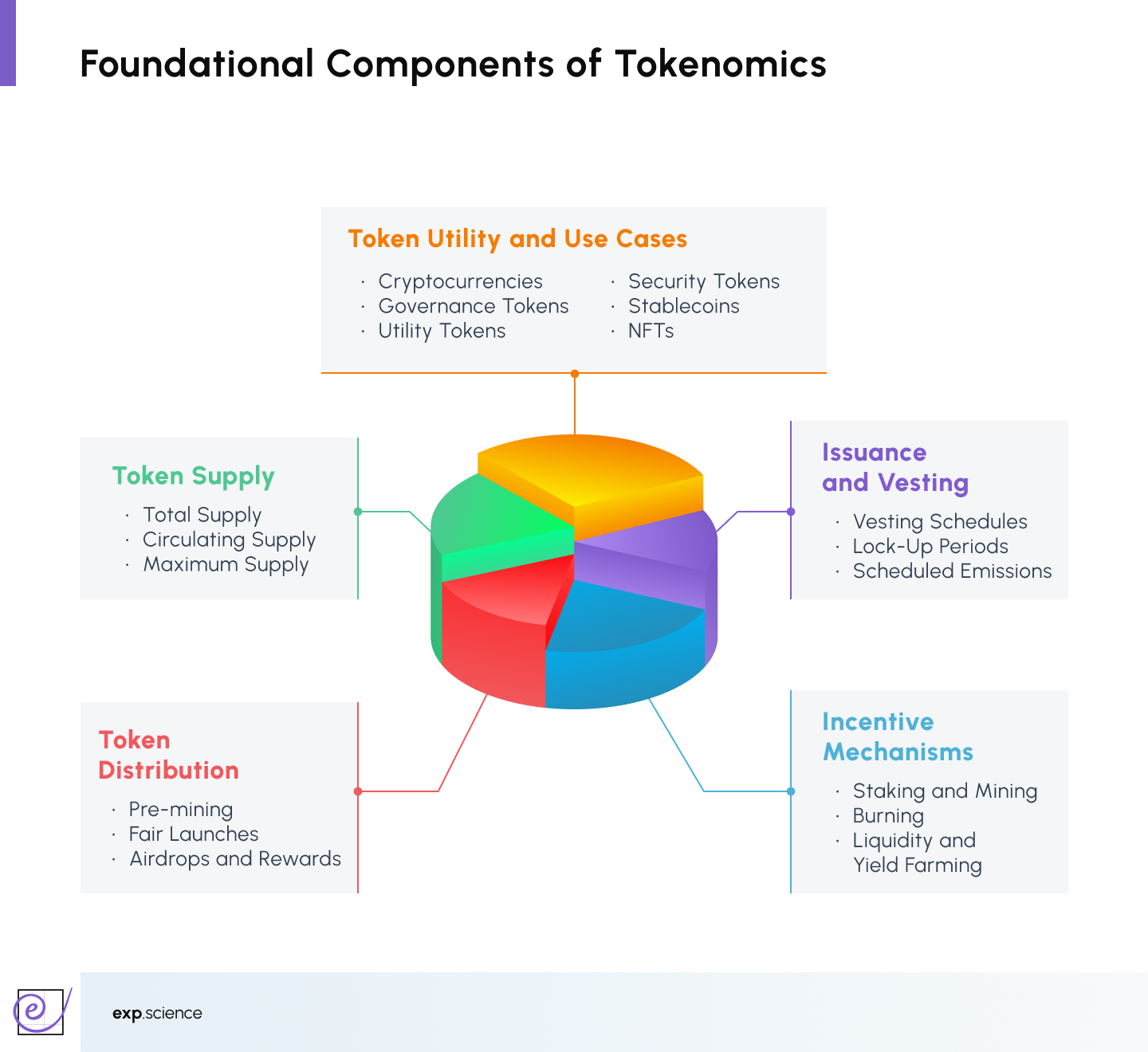

Key Components of Tokenomics

Tokenomics can be broken down into several interrelated components typically outlined in a project’s whitepaper, the foundational document detailing a project’s vision, technical infrastructure, and economic model. These components collectively define how the token operates and sustains its value over time, providing a comprehensive view of the token’s design and overall architecture.

Token Supply

Supply is one of the fundamental drivers of a token’s value and is typically represented by three key metrics:

- Total Supply: The full quantity of tokens currently in existence, excluding any that have been permanently removed from circulation.

- Circulating Supply: The subset of tokens that are currently available for public trading or use. This figure fluctuates based on mechanisms like minting, burning, or vesting.

- Maximum Supply (Hard Cap): The highest number of tokens that will ever exist, if capped.

Scarcity is often used as a value proposition. Bitcoin’s 21 million hard cap on supply is a classic example of a deflationary tokenomics model, where reduced production over time can drive demand. Conversely, tokens without a hard cap, like Ethereum, require active mechanisms to control inflation and avoid dilution of value. In Ethereum’s case, the dynamic model includes burning fees (EIP-1559) to offset new issuance, making the supply more elastic and tied to network activity.

Token Distribution

The way tokens are distributed at the beginning of a project plays a critical role in shaping long-term trust, decentralisation, and market performance. Common distribution models include:

- Pre-mining: Tokens are created and allocated before public access, often to founders, investors, or project treasuries. Common in Layer-1 protocols and DeFi launches.

- Fair launches: All participants have equal access at the point of launch, without privileged allocations. Bitcoin and Dogecoin are well-known examples.

- Airdrops and community rewards: Tokens are distributed freely to early users, active participants, or aligned communities to stimulate adoption and engagement.

A poorly designed distribution can lead to market centralisation, price volatility, or mistrust. Transparency in allocation is essential for long-term sustainability.

Issuance and Vesting

Token issuance schedules and vesting frameworks are crucial to managing supply inflation and aligning long-term incentives:

- Vesting Schedules: These delay the release of tokens to core team members, advisors, or investors. The goal is to reduce early sell-offs and ensure prolonged commitment.

- Lock-Up Periods: Often implemented after an ICO or launch, these prevent tokens from being traded or sold for a set period to protect against short-term speculation.

- Scheduled Emissions: Some projects predefine token issuance over time — for example, through block rewards or time-based releases. This structure helps create predictability and budget planning for both the protocol and investors.

Bitcoin’s halving every four years is a prime example of programmed emissions, while Ethereum adjusts new issuance based on staking participation.

Token Utility and Use Cases

Tokens are the fuel of decentralised ecosystems; they enable the exchange of value, coordinate participation, and align stakeholder incentives. By design, tokens foster activity within protocols, acting as both transactional mediums and strategic tools to access, govern, or incentivise different layers of a blockchain system. Their versatility allows them to fulfil a wide range of functions, and this functional relevance is what defines their utility.

Utility is a cornerstone of a token’s relevance and longevity. The clearer and more embedded the utility, the stronger the demand:

- Cryptocurrencies: Serve as mediums of exchange or stores of value (e.g., BTC).

- Governance Tokens: Enable holders to vote on protocol upgrades, treasury allocations, or fee structures (e.g., AAVE, UNI).

- Utility Tokens: Provide access to services, platforms, or network functions, such as gas fees or usage permissions (e.g., LINK, ETH).

- Security Tokens: Represent real-world assets or digital financial instruments and typically fall under securities regulation (e.g., INX Token).

- Stablecoins: Pegged to fiat currencies, most often USD, to maintain a stable price (e.g., USDT, DAI).

- NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens): Represent digital ownership of unique assets like art, music, or virtual land (e.g., BAYC, CryptoPunks).

Strong utility drives organic demand and reinforces token circulation, while vague or underutilised tokens often become speculative or obsolete.

Incentive Mechanics

These are built into the protocol to guide user behaviour and reward participation. When well-calibrated, they create self-reinforcing loops of activity and value creation:

- Staking and Mining: Participants contribute resources—computing power or capital—to secure the network and receive rewards. Bitcoin uses Proof-of-Work; Ethereum uses Proof-of-Stake.

- Burning: The deliberate removal of tokens from circulation to reduce supply and increase scarcity. Binance’s BNB uses periodic burns to maintain scarcity.

- Liquidity and Yield Farming: Users provide capital to liquidity pools or strategically deploy tokens across DeFi protocols to earn rewards. These models fuel decentralised finance ecosystems and are prevalent in platforms like Uniswap, Curve, and Compound.

Incentive mechanisms draw from behavioural economics and game theory. However, unsustainable reward models can result in inflation or attract speculative actors rather than loyal users.

Liquidity: The Safety Net against Volatility

Liquidity describes how easily a token can be bought or sold without causing significant price swings. Crypto liquidity is driven by factors such as trading volume, depth in order books, and liquidity available in decentralised exchanges (DEXs).

Low liquidity increases slippage, opens the door to price manipulation, and can block exits during market stress. Consequently, effective tokenomics often weaves in mechanisms that support liquidity provision, such as incentives for liquidity pool contributors or protocol-owned liquidity strategies. With strong liquidity, token usability and investor confidence rise; without it, even well-designed systems can fail under stress.

Cryptocurrency markets are inherently volatile, but tokenomics can mitigate this:

- Inflationary models gradually increase supply, which may reduce value unless matched by demand.

- Deflationary models decrease supply through mechanisms like burning, potentially increasing scarcity and value.

- Stablecoins aim for price stability through collateral reserves or algorithmic control.

Ethereum’s shift to a semi-deflationary model via EIP-1559 (which burns transaction fees) is a prime example of tokenomics used to influence volatility and value perception.

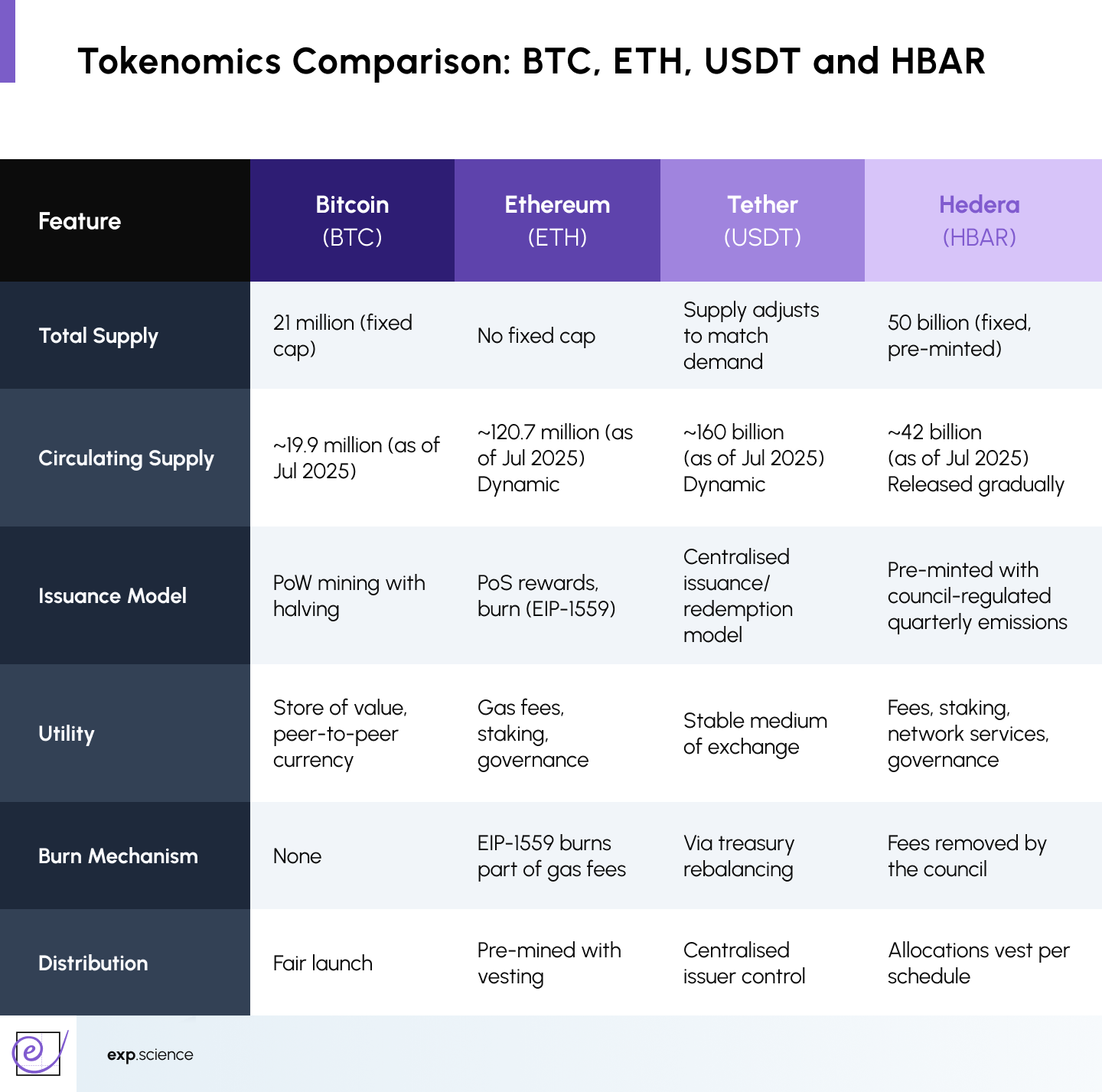

Tokenomics in Practice: A Comparative Overview

To understand how tokenomics models differ in practice, below is a comparison of how Bitcoin, Ethereum, Tether and Hedera structure supply, distribution, utility and how their models differ and do not follow the same model.

Bitcoin’s tokenomics is deflationary and transparent, with a slow and predictable issuance model that prioritises decentralisation. Ethereum’s more complex structure balances flexibility with deflationary mechanisms and broader utility. Tether, meanwhile, operates like a centralised financial instrument, relying on trust in its reserves and an adjustable supply governed by fiat flows. Hedera’s HBAR introduces a hybrid model with its council-governed model, fixed supply, and energy-efficient PoS consensus, designed for predictable, enterprise-grade scalability.

Learn more about Hedera and HBAR 👉 What is Hedera Hashgraph and How HBAR Works?

These distinctions outline how each token aligns with its function: Bitcoin as a monetary alternative, Ethereum as a decentralised platform, Tether as a fiat-backed liquidity tool, and Hedera as a high-throughput network for enterprise and public use.

Red Flags in Tokenomics

Effective tokenomics is not a guarantee of success, but ineffective design often signals failure. Here are some warning signs:

- Unclear Utility: Tokens without well-defined use cases attract minimal interest or traction.

- Excessive Insider Allocation: A high concentration of tokens in founders or investors risks market manipulation and centralised control.

- Unsustainable Rewards: Tactics promising very high APYs (Annual Percentage Yields) or returns can indicate Ponzi-style dynamics.

- Opaque Token Design: Lack of detailed documentation, vesting terms, or clear tokenomics metrics undermines investor confidence.

- Missing Long-Term Plan: Tokens without a sustainable strategy for ongoing use, value extraction, or supply sinks tend to lose momentum once initial interest fades.

Due diligence on tokenomics is a vital step before investing, especially in early-stage projects.

Tokenomics as Digital Architecture

Tokenomics serves as the economic architecture of blockchain ecosystems. It determines how value flows, who captures it, and how the system maintains itself over time.

For developers, it provides the blueprint. For investors, it is the valuation lens. For communities, it serves as a trust mechanism.

Whether deflationary assets like Bitcoin, utility-driven like Ethereum, stabilised like Tether or enterprise-optimised like Hedera, tokenomics encodes a project’s strategic vision. However, even the best-designed models are vulnerable to macroeconomic shifts, regulation, and sentiment. Ultimately, tokenomics is not a silver bullet; it coexists with sound governance, risk management, and real-world utility.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)