Robotics is one of the most transformative frontiers in modern technology. It combines mechanical systems, electrical engineering, software, sensing and artificial intelligence (AI) to produce machines that assist, augment or even replace human tasks. In doing so, robotics bridges the physical and digital worlds, where hardware meets autonomous decision-making.

Robotics is the branch of engineering and computer science devoted to designing, building and operating machines capable of performing tasks (often those traditionally carried out by humans) either autonomously or under supervision. These systems are developed to extend human capability, particularly where speed, precision or safety are critical.

It sits at the intersection of multiple technical fields, combining physical mechanics with computing and intelligence to produce machines that can sense, decide and act. From factory lines to personal homes, robots today vary widely in form and function, yet share the goal of interacting effectively with the real world.

Key characteristics help define the field and its evolving role in society:

- Interdisciplinary Foundations: Robotics integrates mechanical design, electronics, software and control theory to coordinate hardware and intelligent behaviour.

- Human Augmentation: Robots support or substitute human labour in repetitive, risky or highly precise tasks.

- Iterative Development: Systems improve through ongoing design, testing and adaptation.

- Degrees of Autonomy: Robotic platforms range from fully manual to fully autonomous, depending on application and context.

- Technological Convergence: Robotics increasingly incorporates AI, IoT connectivity, and real-time data to navigate dynamic environments and make decisions.

👉 Learn more about these convergences: Blockchain, AI and Sustainability: How Emerging Technologies Converge

Core Building Blocks of a Robotic System

Robots take many forms, from surgical assistants to autonomous vacuum cleaners, yet all share a common foundation of key functional modules:

Mechanical Structure and Kinematics: The robot’s physical framework - its joints, limbs, wheels, tracks or legs, and any tools or grippers it uses to interact with its environment. The mechanical design must suit the intended task, whether navigating uneven terrain or assembling fine components on a production line.

Power and Actuation: Movement relies on actuators that convert energy into motion, such as electric motors, pneumatic systems or hydraulics. The type of actuator depends on the required strength, speed, precision and safety. Power sources (batteries, mains or alternatives) must be chosen to match energy demands and constraints.

Sensing: Robots rely on a diverse range of sensors to perceive the world around them. These include visual systems (cameras, depth sensors, LIDAR), proximity detectors, tactile and force sensors for physical interaction, thermal sensors, position encoders, and inertial measurement units (IMUs) that detect motion and orientation. Such real-life data is essential for situational awareness and responsive behaviour.

Computation, Control and Software: The ‘brain’ of the robot consists of embedded processors and software that interpret sensor data, plan actions and control motion. Core algorithms handle perception, decision-making and motion planning, transforming inputs into appropriate outputs via feedback loops. The overall process follows a cycle of: sense - process - act.

Autonomy and Human Interaction: Robots operate at varying levels of independence. Some are fully teleoperated; others follow scripted routines or adapt to their environment using AI. As they increasingly collaborate with people, robots must ensure safe and intuitive interaction through interfaces, safeguards and real-time responsiveness. Systems designed for shared workspaces often blend autonomy with human oversight.

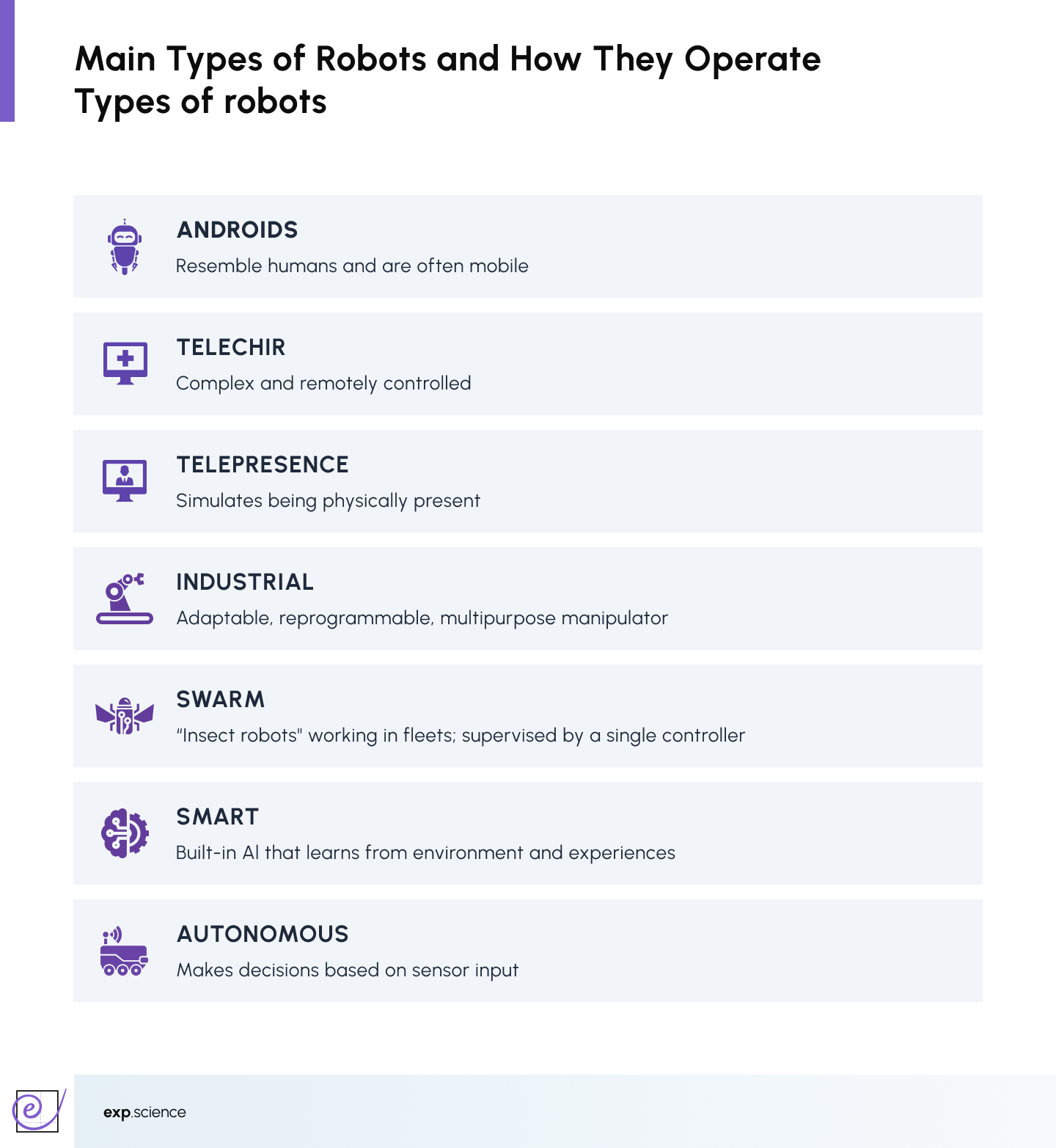

From Androids to Autonomous Systems: Robot Types

Robots can be classified in multiple ways: by their physical form, mobility, how they interact with people and systems, and their level of autonomy. These categories are not mutually exclusive; in practice, a robot might span several types. For example, a collaborative industrial arm could be both teleoperated and partially autonomous.

- Androids: Humanoid robots designed to mimic human appearance and behaviour. Typically mobile, they operate in human-centric environments, from reception desks and customer service to academic research into human–robot interaction.

- Telechir: Also known as telemanipulators or ‘master–slave’ systems, these robots are remotely controlled by a human operator, often with haptic feedback to simulate touch. They’re used in precision-critical or hazardous environments such as surgery, deep-sea maintenance or radioactive handling.

- Telepresence: Robots that act as mobile surrogates, allowing a remote user to interact with distant environments. Equipped with cameras, screens, microphones and speakers, they’re commonly used in healthcare, remote education, site inspections and virtual meetings.

- Industrial: Reprogrammable manipulators built for tasks like welding, painting, assembly and material handling. These include articulated arms, SCARA, delta and Cartesian robots. Collaborative versions (cobots) are designed to work safely alongside humans.

- Swarm: Groups of relatively simple robots that coordinate their actions based on shared rules or distributed algorithms. Swarms are used for scalable tasks such as area mapping, search and rescue, or environmental monitoring, offering robustness through redundancy.

- Smart: Robots enhanced with artificial intelligence that are able to learn from data and improve over time. Through sensor fusion and machine learning, they adapt to dynamic environments without every decision being manually coded.

- Autonomous: Systems capable of perceiving, planning and acting with minimal human intervention. They operate in real time using sensor data, often incorporating AI to navigate uncertainty. Most still include safeguards and manual override features for safety and accountability.

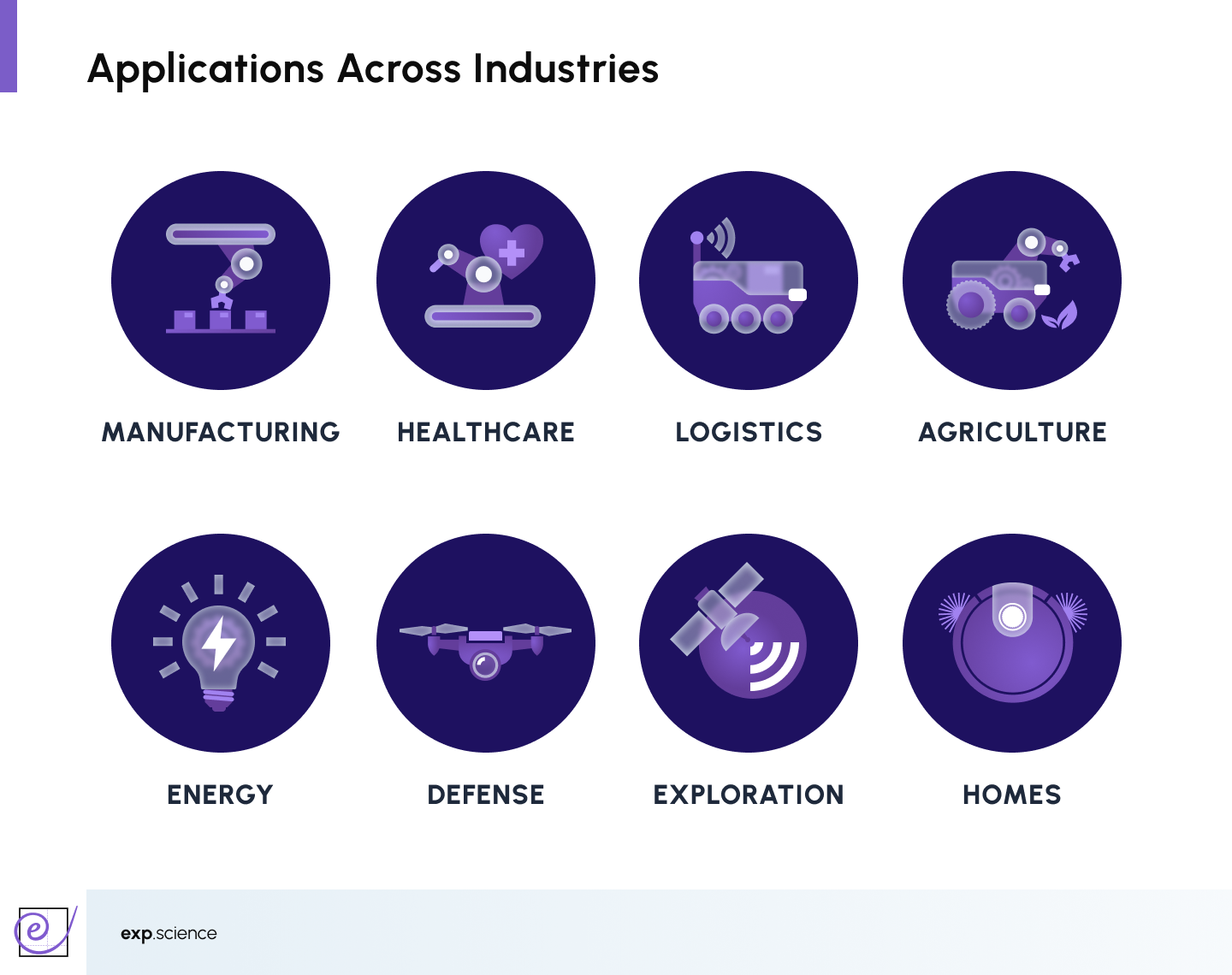

Applications Across Industries

Robotics has become integral to a wide range of sectors, creating tangible value through efficiency, precision and automation. Below are key domains where robots are actively transforming operations and outcomes:

Manufacturing and Industrial Operations

Robots enhance throughput, product quality and consistency in tasks such as assembly, welding and finishing. Fixed manipulators handle high-volume work, while collaborative robots (cobots) and autonomous mobile robots (AMRs) enable flexible production, late-stage customisation and streamlined intralogistics, often without costly retooling.

Healthcare and Life Sciences

Robotics enhances surgical accuracy and repeatability, assists with hospital logistics and sterilisation, and accelerates diagnostics through lab automation. Rehabilitation and assistive robots support patient independence, while AI-enabled systems help clinicians manage workloads with greater safety and traceability.

Logistics, Retail and E-Commerce

In warehouses and distribution centres, robots speed up order fulfilment, inventory checks and goods transportation. AMRs navigate dynamic layouts and seasonal demand, while orchestration software coordinates human workers, mobile fleets and fixed systems to maximise efficiency.

Agriculture and Natural Resources

Agricultural robots improve yields and resource use through crop monitoring, precision spraying and selective harvesting. Equipped with GPS and multi-spectral vision, field robots operate at the plant level, while drones provide aerial insights to guide irrigation, fertilisation and pest control.

Energy, Utilities and Critical Infrastructure

Robots minimise inspection risks in hazardous or remote areas, such as turbines, offshore rigs or pipelines, by capturing high-resolution visual, thermal and sonar data. These insights support predictive maintenance and reduce human exposure during dangerous tasks.

Public Safety, Defence and Disaster Response

In emergencies and conflict zones, robots extend operational reach for reconnaissance, explosive disposal, and search-and-rescue operations. Ground units and aerial drones provide situational awareness in unstable or high-risk environments, protecting first responders from harm.

Science, Space and Marine Exploration

Robotic platforms enable long-term exploration in environments beyond human reach, from deep-sea vents to planetary surfaces. These systems collect data for disciplines such as geology, biology and climate science, often operating autonomously for extended periods.

Homes and Personal Services

Consumer robots provide everyday support through automated cleaning, lawn care and basic assistance. In eldercare and telepresence, they offer companionship, mobility aid and remote interaction. Design emphasises safety, ease of use and reliability in unpredictable domestic settings.

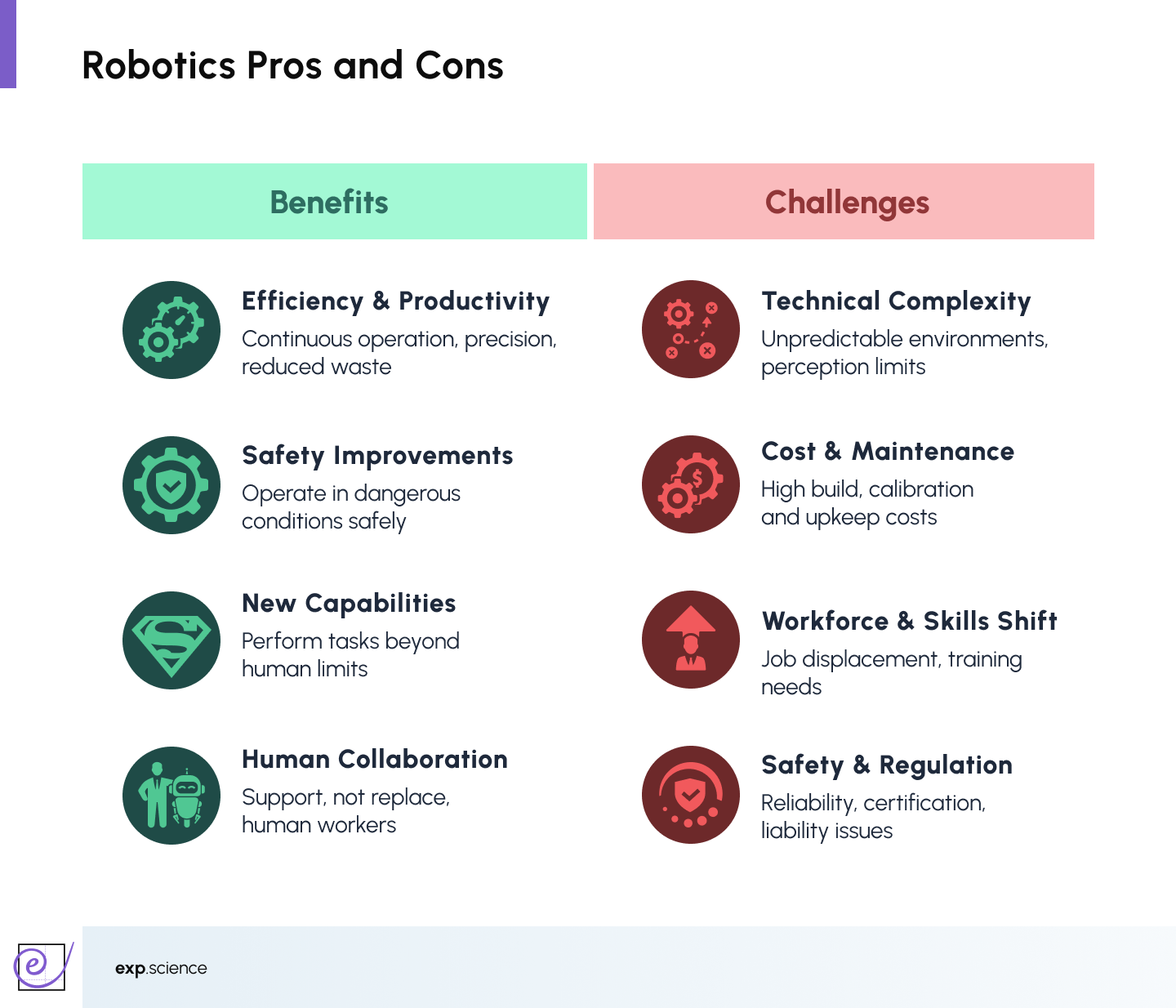

Robotics Opportunities and Challenges

Robotics offers significant advantages across industries:

- Productivity and Efficiency: Robots operate continuously with high speed and precision, increasing output while reducing waste and downtime.

- Enhanced Safety: They take on dangerous tasks —in hazardous, toxic, or extreme environments— lowering risks for human workers.

- New Capabilities: From microscopic manipulation to deep-sea and space exploration, robots enable tasks beyond human reach.

- Human–Machine Collaboration: Collaborative robots ('cobots') work alongside people, freeing them to focus on creative, strategic or emotionally nuanced roles.

- Technology Acceleration: Advancements in robotics fuel progress in AI, sensors, connectivity and materials, driving broader innovation ecosystems.

Despite their potential, robotics also brings technical, economic and ethical hurdles:

- System Complexity: Robots still struggle in dynamic, unstructured environments where human adaptability remains superior.

- Costs and Maintenance: High initial investment, ongoing upkeep, and downtime can limit adoption, especially for smaller organisations.

- Labour and Skills Shift: Automation may displace jobs while creating demand for new technical roles, raising social and economic questions.

- Safety, Ethics and Trust: Reliability, regulation and public confidence are essential, particularly for autonomous systems operating near people.

- Scalability and Integration: Many systems are task-specific; achieving interoperability, modularity, and scalable deployment remains a major challenge.

Final Thoughts: Building the Right Robots for the Future

A strategic vector for innovation, convergence and societal impact, Robotics represents a paradigm shift in how humans interact with machines and environments. From the factory floor to the operating theatre, from home assistants to autonomous drones, robotics is reshaping industries, workflows and daily life.

In the next decade and beyond, robots will increasingly transition from isolated tools to integrated collaborators; from novelty to new normal; embedded in our infrastructure, workplace, homes and lives. Understanding these machines means understanding both their technical foundations (mechanics, sensors, control, software) and their strategic context (applications, opportunities, risks, human‑machine interface, organisational impact).

As the field matures, the challenge will be to deploy robots that are safe, adaptable, connected and aligned with human values.

.webp)

.jpg)

.jpg)