A blockchain consensus mechanism is a set of rules or algorithms that enables a network of computers (nodes) to agree on the validity of new transactions and the current state of the shared ledger, ensuring data integrity and consistency without a central authority. These mechanisms use various models, such as Proof-of-Work (PoW) or Proof-of-Stake (PoS), to achieve this agreement, prevent fraudulent activity, and maintain a single, trusted version of the blockchain.

Think of a consensus mechanism being a group of friends trying to split a restaurant bill. Everyone at the table needs to agree on what was ordered, how much it cost, and who owes what. To make sure no one cheats or makes mistakes, they might pass the receipt around for everyone to verify (like Proof-of-Work where everyone puts in an effort to check), or they might trust the person who's been most reliable with money in the past to tally it up (like Proof-of-Stake - giving authority to those with the most ‘stake’ in being honest). Either way, they all reach an agreement on the final bill without needing a manager to tell them what's true, they figure it out together and everyone accepts the result.

Bitcoin introduced the first decentralised blockchain consensus mechanism (PoW) in 2008, developed by Satoshi Nakamoto. However, the concept of consensus in distributed systems existed long before Bitcoin. Earlier research addressed trust and agreement among participants, such as works by David Chaum (1982) and Haber & Stornetta (1991), and Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT) algorithms in computer science.

What Is Consensus?

Before diving into the technical details, let's consider what consensus actually means. In everyday life, consensus is how groups make decisions when everyone needs to agree, such as friends choosing which restaurant to dine at. But consensus in distributed computer systems faces a unique challenge. When computers need to agree on something, like whether a transaction is valid, they face a problem: how do you know what's true when you can't trust your sources of information?

Determining what is blockchain consensus becomes even more vital when considering that some computers in the network might be deliberately malicious or faulty. How can a system reach an agreement when some participants are lying? This is fundamentally a problem about creating truth in an adversarial environment, and it's been puzzling computer scientists for decades.

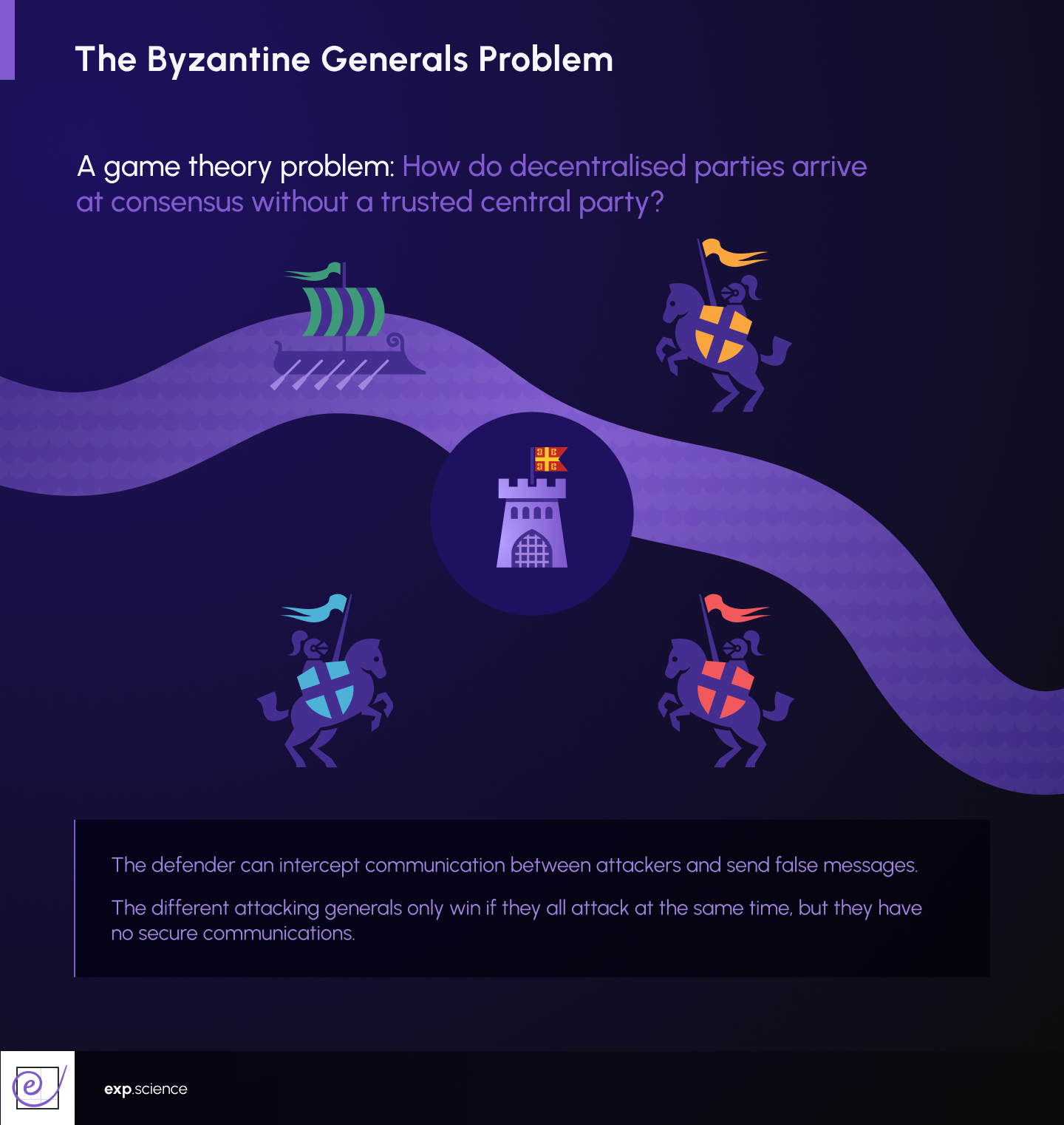

The Byzantine Generals Problem

The modern story of consensus mechanisms begins in 1982 with a thought experiment called the Byzantine Generals Problem, conceived by computer scientists Leslie Lamport, Robert Shostak, and Marshall Pease at SRI International in California.

The scenario goes like this: several divisions of the Byzantine army are camped outside an enemy city, each led by a general. The generals can only communicate by messenger, and they must agree on a coordinated plan: attack or retreat. The problem is that some generals might be traitors who send different messages to different commanders, trying to sabotage the plan. How can the loyal generals reach consensus despite the potential presence of traitors?

In a network of computers, some might fail or be compromised. Messages might get delayed or corrupted. Yet the system still needs to agree on what's happening. The Byzantine Generals Problem formalised this challenge and proposed mathematical solutions.

The researchers showed that if a group consisted of a certain number of generals, the system could handle up to one-third of them being traitors, provided the generals communicated using only oral messages. Their work laid the theoretical foundation for all modern consensus mechanisms, establishing that consensus was mathematically possible even in adversarial conditions.

However, their solutions were computationally expensive and difficult to implement in real-world systems. The breakthrough would come later, when these theoretical insights met practical necessity.

Distributed Systems and the Need for Agreement

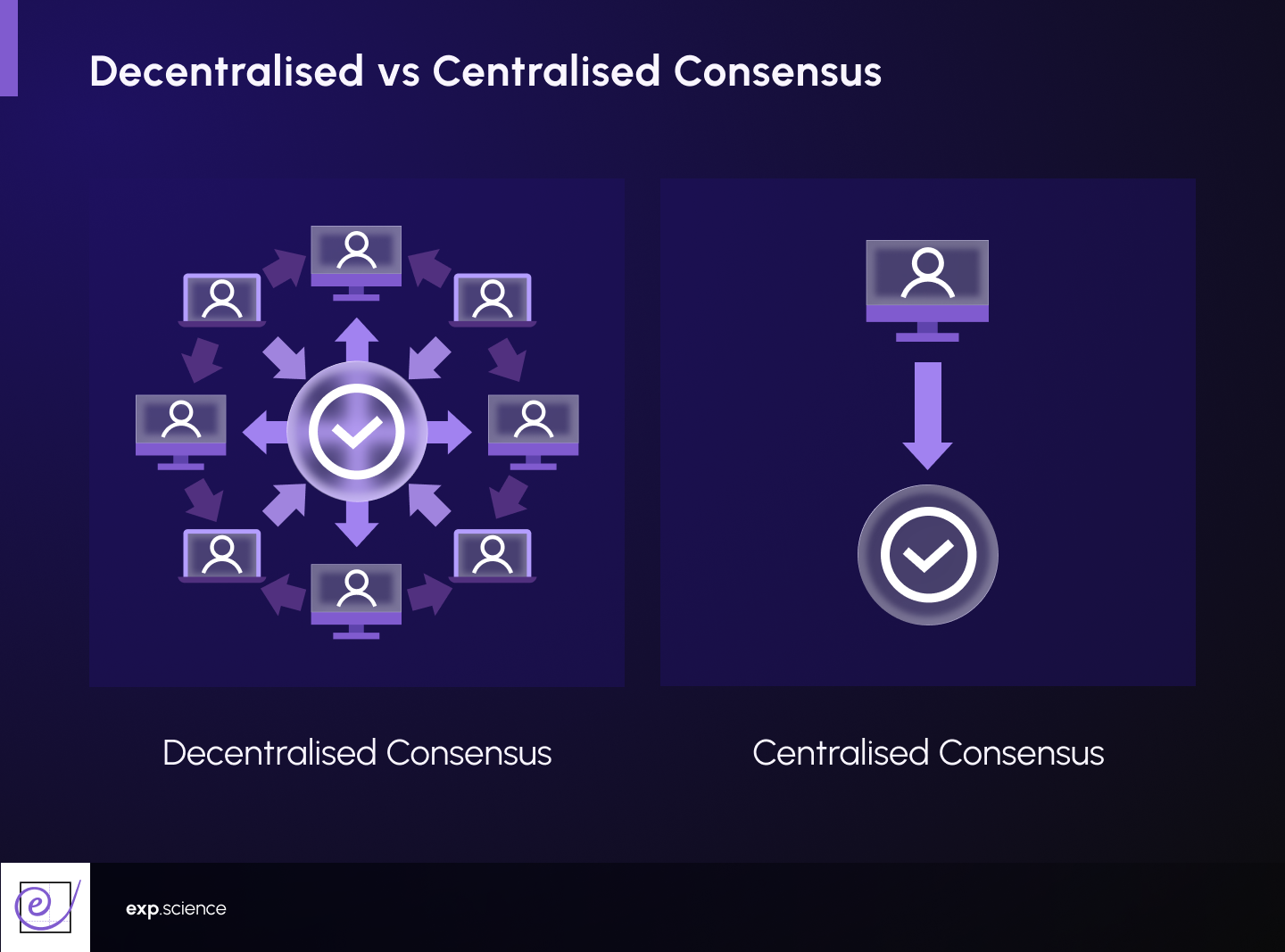

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, as computer networks expanded, the need for consensus mechanisms grew. Databases spread across multiple servers need to stay synchronised. Distributed systems require ways to coordinate actions. But most solutions relied on a central authority, a master server that made final decisions.

This centralised approach had obvious weaknesses. If the central authority failed, the entire system failed. If it was compromised, the whole network was vulnerable. And philosophically, it contradicted the promise of distributed systems: that power and control could be decentralised.

Computer scientists developed various consensus protocols for distributed databases, including Paxos (developed by Leslie Lamport in 1989 but not published until 1998) and later Raft. These allowed distributed systems to reach agreement without a single point of failure. However, they were designed for closed systems where participants were known and generally trusted. They couldn't handle a truly open network where anyone could join and where participants might be actively malicious.

Enter Satoshi Nakamoto and Bitcoin

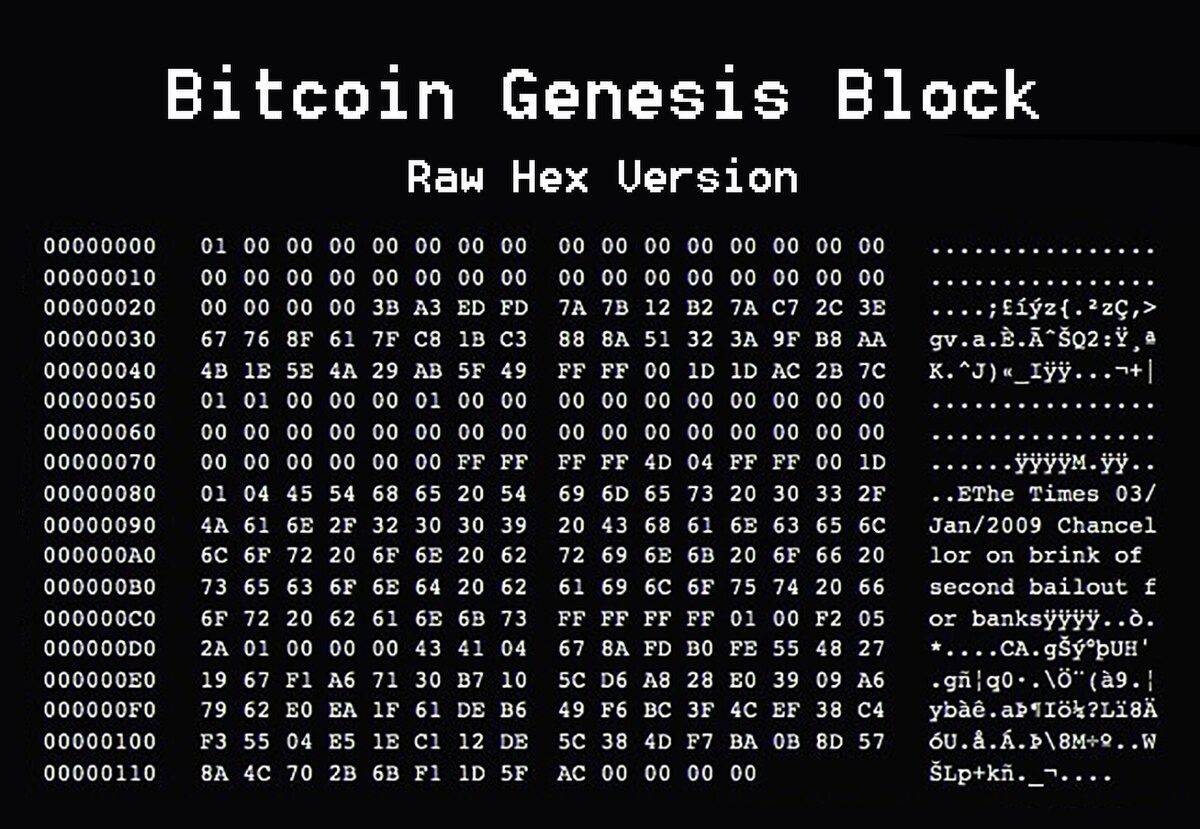

On 31 October 2008, someone using the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto published a whitepaper titled ‘Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System,’ a nine-page document that would change history.

Nakamoto's innovation was combining cryptography, distributed systems theory, and economic incentives to create the first practical solution for consensus in a completely open network. The PoW mechanism allowed thousands of anonymous computers to agree on the order and validity of transactions without trusting each other or relying on a central authority.

The brilliance of Nakamoto's approach was in its simplicity. Instead of trying to prevent bad actors from participating, the system made it prohibitively expensive to cheat. Here's how it works: Computers called ‘miners’ compete to solve difficult mathematical puzzles. The winner gets to add the next block of transactions to the blockchain and receives a reward in Bitcoin. The puzzle is designed to be hard to solve but easy to verify, like a jigsaw puzzle is difficult to complete but easy to check once finished.

The security element comes from the computational work required. If someone wanted to change historical transactions, they'd need to redo all the computational work from that point forward, and do it faster than the rest of the network combined. The more computers mining honestly, the more expensive it becomes to attack the system.

This was consensus through computation. By making miners invest real-world resources (electricity and hardware), Nakamoto created a bridge between the digital and physical worlds. You couldn't cheat the system without spending real money, and as long as the rewards for honest behaviour exceeded the costs of cheating, the system remained secure.

Why This Mattered for Cryptocurrency

Nakamoto's consensus mechanism solved a problem that had plagued previous attempts at digital currency: the double-spend problem. In the physical world, if you give someone a $10 note, you no longer have it, you can't spend it again. But digital information can be copied infinitely. How do you prevent someone from spending the same digital coin twice?

Previous digital currency attempts solved this by having a central authority track all transactions, ensuring each coin was only spent once. But this recreated the problems of traditional banking: you had to trust the central authority, which could freeze your account, track your spending, or fail and take your money with it.

Bitcoin's consensus mechanism meant that the entire network collectively maintained the transaction ledger. Every participant could verify that coins hadn't been double-spent by checking the blockchain. No central authority needed, no single point of failure, no one to trust.

For the first time in history, people could exchange value digitally without an intermediary. The consensus mechanism made trustless trust possible, you didn't need to trust any individual or institution, only the mathematics and the assumption that the majority of network participants acted in their own economic self-interest.

Distributed Ledger Technology Emerges

Bitcoin demonstrated that consensus mechanisms could do more than just run a cryptocurrency, but also maintain a shared database in a hostile environment. This realisation gave birth to distributed ledger technology (DLT) and blockchain technology as a broader field.

A distributed ledger is simply a database shared across multiple locations without central administration. The consensus mechanism is what makes this possible. It's the rulebook that determines how the ledger gets updated, who can write to it, and how disputes get resolved.

Different applications required different types of consensus mechanisms. Bitcoin's Proof-of-Work worked well for a public, permissionless network where anyone could participate. But it was slow (processing only a few transactions per second), expensive (consuming enormous amounts of electricity), and perhaps overkill for use cases where participants were known and partially trusted. This sparked an explosion of innovation in consensus mechanisms, each trying to balance different trade-offs between security, speed, decentralisation, and energy efficiency.

The Centralisation Paradox

Blockchains can’t simply appoint a single person in charge because their purpose is to prevent any one entity from controlling, censoring, or shutting down the system. Unlike a normal database, which relies on a trusted administrator, blockchains use consensus mechanisms to solve Byzantine fault tolerance: maintaining a reliable system even when some participants are malicious, offline, or incorrect.

PoW’s high energy use was deliberate: by forcing miners to expend real-world energy, Bitcoin makes rewriting history prohibitively expensive, anchoring digital security to physical reality. However, power can still concentrate in fewer hands, and recent events show this risk is real.

For example, a major mining entity temporarily gained majority hash power on Monero in August 2025 and carried out a notable block reorganisation. Although experts disagreed on whether this constituted a full 51 percent attack, the incident clearly underscored the centralisation risks present in Proof-of-Work systems. These issues reflect unavoidable trade-offs between security, decentralisation, and other values, with different communities choosing different compromises.

Different Consensus Mechanisms

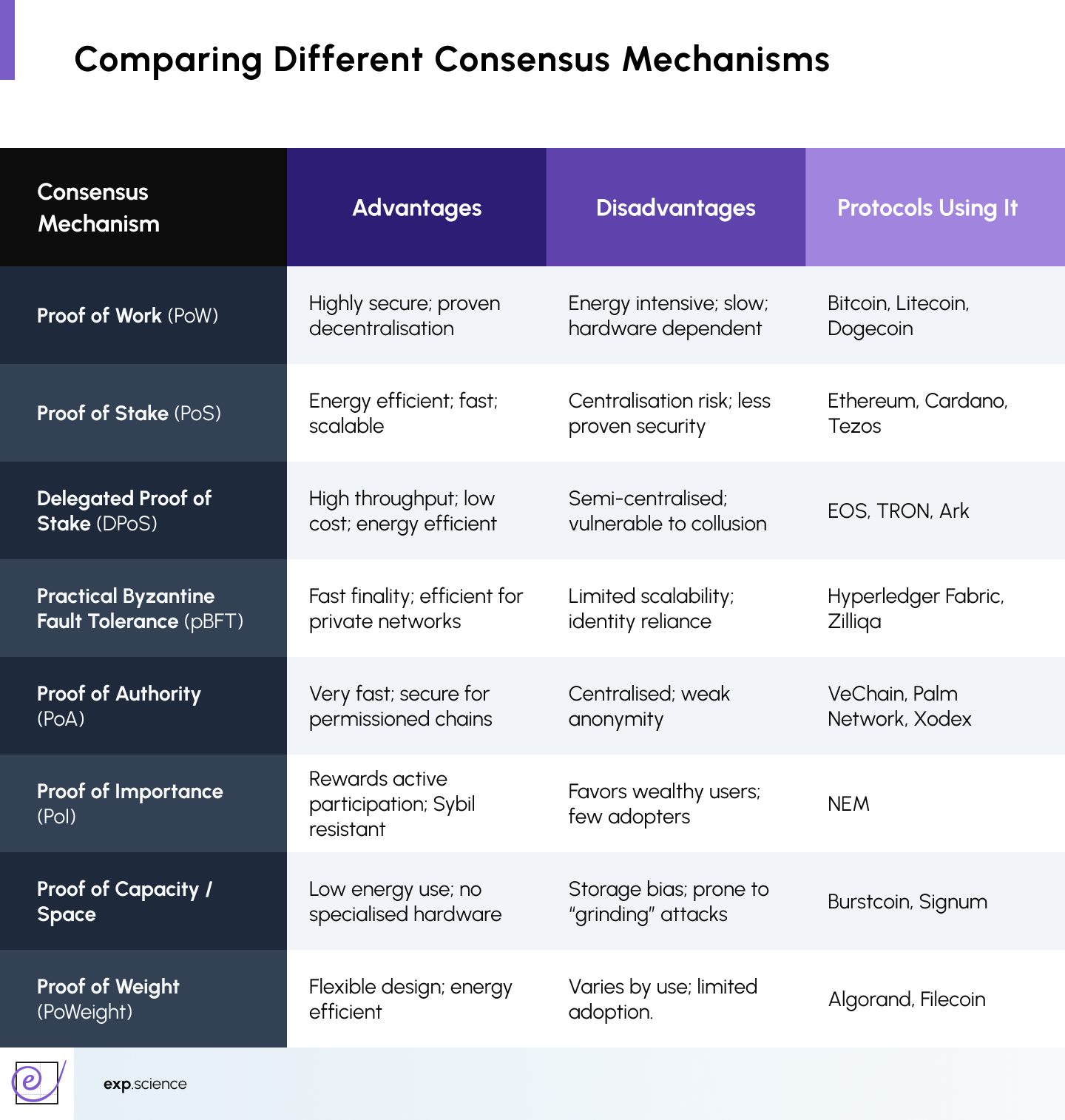

- Proof-of-Work (PoW)

Proof-of-Work, used by Bitcoin and formerly Ethereum, requires participants to expend computational resources. Its advantages are strong security, decentralisation, and a decade of real-world testing. Its drawbacks include high energy use, slower speeds, and costly hardware.

By tying digital assets to physical resource expenditure, some argue it gives them real-world value, while others see it as wasteful electricity spent on pointless puzzles.

- Proof-of-Stake (PoS)

Proof-of-Stake selects validators based on the coins they ‘stake’ as collateral, the more you stake, the higher your chance to validate a block and earn rewards. Fraudulent behaviour risks losing your stake, creating security through economic incentives rather than computation.

Ethereum’s switch to Proof-of-Stake in September 2022 cut its energy use by over 99% while maintaining security. Projects like Cardano and Polkadot use it from the start. Critics say it favours the wealthy and lacks physical grounding, but supporters highlight its accessibility and sustainability.

- Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPoS)

A variation where coin holders vote for a small number of delegates who validate transactions on everyone's behalf. It's faster and more energy-efficient than traditional Proof-of-Stake, but more centralised. EOS and TRON use this mechanism.

The trade-off is explicit: sacrifice some decentralisation for speed and efficiency. It's philosophically closer to representative democracy than direct democracy.

- Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT)

PBFT, developed in 1999 by Miguel Castro and Barbara Liskov, provides practical Byzantine fault tolerance. Nodes vote through multiple rounds to reach consensus. It’s fast and energy-efficient, but requires a known set of validators and scales poorly.

PBFT suits private or consortium blockchains, like Hyperledger Fabric, for shared ledgers in supply chains or inter-bank settlements.

- Proof-of-Authority (PoA)

Here, a limited number of pre-approved validators maintain the network. It's extremely fast and efficient, but completely abandons decentralisation. The security relies entirely on the reputation and trustworthiness of the validators.

This is useful for private blockchains where participants are known entities, perhaps different departments within a company or a consortium of organisations with existing relationships. The shift is away from ‘trustless’ systems back towards trusted (but auditable) relationships.

Use Cases Beyond Cryptocurrency

Whilst consensus mechanisms were developed for cryptocurrency, their applications extend far beyond digital money.

Supply Chain Management

Global companies like Walmart and Maersk use distributed ledgers with consensus mechanisms to track products from manufacture to delivery. Every time goods change hands, the transaction is recorded and verified. This creates transparency, reduces fraud, and helps quickly identify problems (like contaminated food or counterfeit goods).

The consensus mechanism ensures that no single party can falsify records. If a supplier claims they shipped 1,000 units but the distributor records receiving only 800, the discrepancy is visible to all parties.

Digital Identity

Estonia has pioneered using distributed ledger technology for national digital identity systems. Citizens can securely access government services, vote electronically, and sign documents digitally. The consensus mechanism ensures that identity records can't be tampered with by any single government agency or hacker.

This has profound implications for privacy and sovereignty. Your identity isn't controlled by a corporation or entirely by a government, it's cryptographically secured and distributed across multiple systems.

Healthcare Records

Medical records are scattered across hospitals, clinics, and laboratories. Consensus mechanisms could enable a distributed system where you control your own health data, granting temporary access to healthcare providers as needed. The records would be tamper-proof and available anywhere, potentially saving lives in emergencies.

Voting Systems

Several countries and organisations are experimenting with blockchain-based voting. The consensus mechanism ensures votes can't be altered after being cast, whilst maintaining voter privacy through cryptography. The challenge is balancing transparency (anyone can verify the election) with privacy (no one can see how you voted).

Smart Contracts and Decentralised Finance (DeFi)

Ethereum popularised ‘smart contracts,’ programs that automatically execute when conditions are met. The consensus mechanism ensures these programs run exactly as written, without interference. This has spawned Decentralised Finance, where people lend, borrow, and trade assets without traditional financial intermediaries.

The philosophical implications are staggering. Code becomes law, in a sense. There's no judge to appeal to, no regulator to petition. The agreement executes automatically, exactly as programmed. This raises new questions about justice, fairness, and what happens when code contains bugs or embodies discriminatory logic.

The Trilemma: Security, Decentralisation, and Scalability

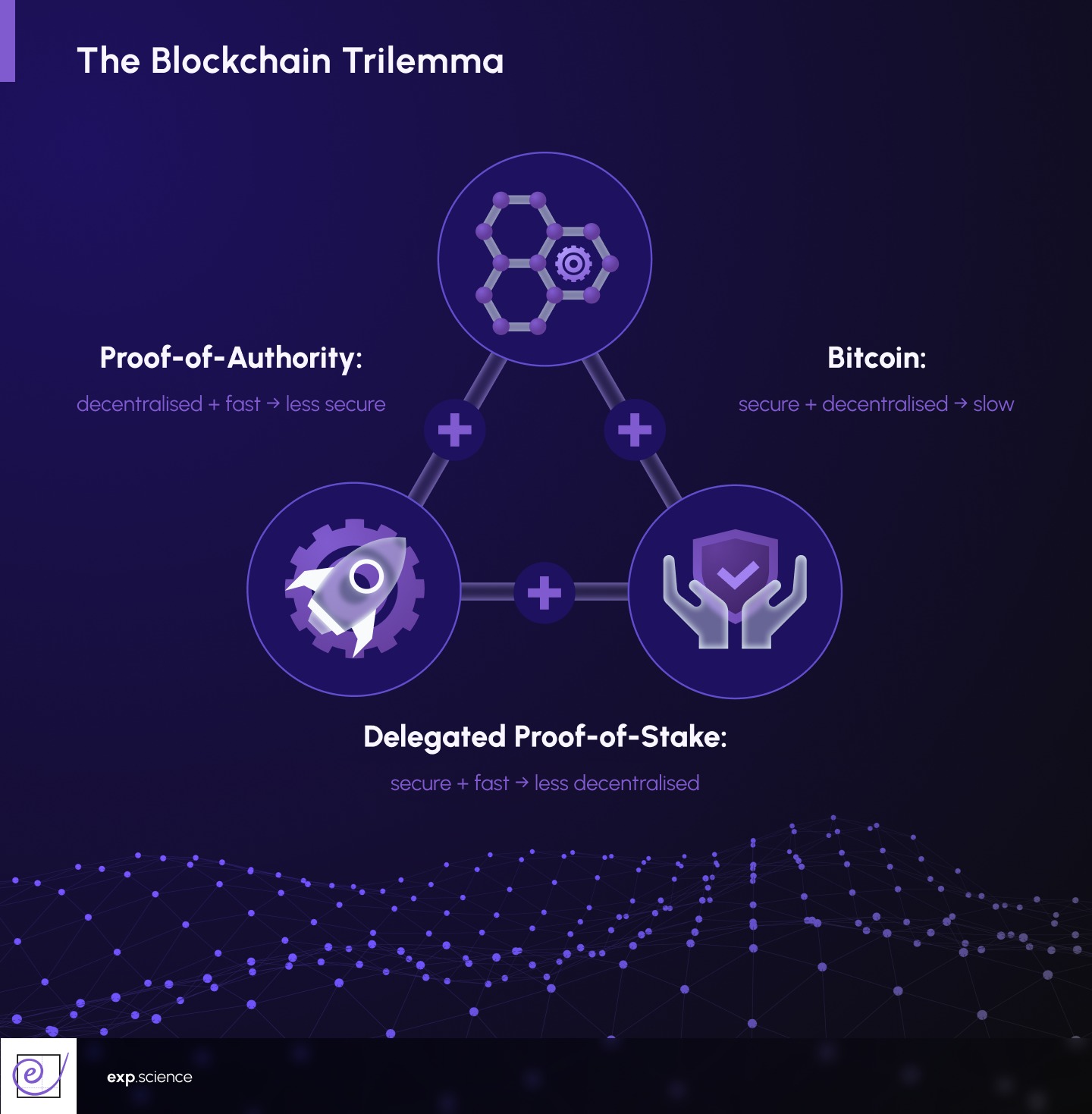

Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin articulated what's become known as the blockchain trilemma: it's extremely difficult to achieve security, decentralisation, and scalability simultaneously. Most consensus mechanisms optimise for two whilst sacrificing the third.

Bitcoin prioritises security and decentralisation but sacrifices scalability (processing only about seven transactions per second). Delegated Proof-of-Stake systems achieve security and scalability but sacrifice decentralisation. Proof-of-Authority achieves decentralisation (if you count the approved validators) and scalability, but relies on trust rather than cryptographic security.

This isn't just a technical challenge, it reflects fundamental trade-offs in how collective decision-making is organised. Should there be systems that are totally open but slow? Fast but controlled? Secure but expensive?

These questions mirror debates humanity has grappled with throughout history: How should freedom and order be balanced? Efficiency and fairness? Individual rights and collective good?

Environmental and Social Considerations

The environmental impact of Proof-of-Work has become increasingly controversial. Bitcoin mining currently consumes more electricity than some countries. As climate change intensifies, this raises ethical questions about whether the benefits justify the costs.

Proponents argue that Bitcoin mining mostly uses renewable or otherwise wasted energy (like natural gas that would be flared off at oil wells). They also contend that the energy secures a financial system serving millions, which should be compared to the energy consumption of traditional banking infrastructure. Critics point out that regardless of the energy source, consuming electricity for Bitcoin mining means it's not available for other uses. The opportunity cost is real.

The shift towards Proof-of-Stake and other energy-efficient mechanisms suggests the industry is taking these concerns seriously. But it also raises the question: if security can be achieved without Proof-of-Work, what exactly was all that energy spent on?

The Future of Consensus

Research into consensus mechanisms continues rapidly. Some promising developments include:

- Layer 2 Solutions: Systems like the Lightning Network for Bitcoin or rollups for Ethereum handle many transactions off the main blockchain, only occasionally syncing with the main chain. This allows the base layer to remain secure and decentralised whilst achieving much higher transaction throughput.

- Sharding: Splitting the blockchain into multiple parallel chains (shards) that can process transactions simultaneously. Ethereum 2.0 is implementing this, potentially increasing capacity enormously.

- Hybrid Mechanisms: Combining different approaches. For instance, some systems use Proof-of-Work to establish initial consensus, then switch to Proof-of-Stake for finality.

- Quantum-Resistant Mechanisms: As quantum computers develop, they may threaten current cryptographic methods. Researchers are developing consensus mechanisms that would remain secure even against quantum attacks.

The Implications: Trust, Truth, and Power

At its core, consensus mechanisms address fundamental questions about how humans coordinate and determine truth. Throughout history, humanity has relied on authorities to establish what's true and enforce agreements. There was little choice, large-scale coordination without central authorities was practically impossible. Consensus mechanisms offer an alternative, shifting power from institutions to protocols.

But is this actually more democratic, or does it simply replace one form of power with another? Those who design consensus mechanisms wield enormous influence, whilst those with more computational power (in PoW) or more coins (in PoS) have more say. The technology-literate gain advantages over others.

The deeper insight is that consensus mechanisms make power structures explicit and auditable. In traditional systems, power often operates invisibly through unwritten rules and closed-door decisions. Consensus mechanisms encode rules in publicly inspectable software. There's also something profound about creating agreement through economic incentives rather than moral authority, these systems don't require participants to be honest, only to find honesty more profitable than cheating.

From Concept to Impact

Consensus mechanisms emerged from theoretical computer science, proved their worth in cryptocurrency, and are now reshaping how trust and coordination are perceived the digital age. They've demonstrated that decentralised coordination is possible at previously unimaginable scales, where strangers cooperate without intermediaries and rules are enforced by mathematics rather than authority.

Yet they raise profound questions: What does it mean to trust mathematics rather than institutions? How to ensure decentralised systems serve justice and fairness? Who decides the rules, and how to change them when needed?

The answers will shape not just technology's future, but how humans organise, exchange value, and determine truth. From the Byzantine Generals Problem to Bitcoin, consensus mechanisms represent a genuine innovation in human coordination, as significant as double-entry bookkeeping or the joint-stock company. The story is still being written, but the core insight remains revolutionary: creating agreement without authority, trust without intermediaries, and truth through mathematics.

.webp)

.jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)